Nationally Recognized. Locally Crafted.

Sep 26, 2018

Since 1960, Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park’s local staff has worked together with a national network of designers, directors and performers to deliver amazing stories and masterful performances for the Greater Cincinnati community. For each production, a team of nationally recognized designers partners with our resident crew at the Gilbert Avenue Scene Shop to bring to life the world of the story as envisioned by the director.

who oversees a team of more than 15 local, union artisans, engineers and craftsmen who work full-time all season long, sometimes alongside extra over-hire staff when more hands are needed on deck. Among the team are carpenters, swings, assistant scenic artists and properties assistants, as well as Technical Director D.W. Jones, Assistant Technical Director Haley Schutzenberger, Charge Scenic Artist Kenton Brett and Properties Manager Liz Lyons. Bishop is among the few women across the country who now run a professional regional theatre scene shop.

who oversees a team of more than 15 local, union artisans, engineers and craftsmen who work full-time all season long, sometimes alongside extra over-hire staff when more hands are needed on deck. Among the team are carpenters, swings, assistant scenic artists and properties assistants, as well as Technical Director D.W. Jones, Assistant Technical Director Haley Schutzenberger, Charge Scenic Artist Kenton Brett and Properties Manager Liz Lyons. Bishop is among the few women across the country who now run a professional regional theatre scene shop.

“When you buy a ticket or contribute to the Playhouse, you are supporting local artisans and local employment, because the artists who build, the stage managers who stage manage and the technicians who run the show and create the sound are all residents of the Greater Cincinnati area,” Bishop explains. “There’s a lot of investment for the folks here at Playhouse in our product because we’re making it for our community, for our neighbors. There’s a lot of pride.”

This season alone, the Playhouse Scene Shop will build sets that range from an isolated cabin in Colorado to a regency manor in England; from a tiny house-in-progress in Oregon to a restaurant in 1969 Pittsburgh; and even the animated world of Charlie Brown and the Peanuts gang. To accomplish this annual feat of building 14 unique, high-quality sets — 11 mainstage productions and three Off the Hill touring plays — they’ll team up with nationally recognized designers who have international and award-winning credits to their names.

“They bring a wonderful, diverse tapestry of ideas and lessons from all the other theatres across the country where they work,” explains Bishop. “We’re hiring designers from Chicago, New York and California who work for other theatres and in television, film, cruise ships and amusement parks. The gentleman who designed A Christmas Carol — James Leonard Joy — has designed extensively for Broadway and the Walt Disney World Company. That’s invaluable. To have somebody come from a place like Disney with great ideas for the Playhouse stage spurs us to collaborate and come up with different solutions to problems that we would normally solve in a standard way. We can’t afford to do it the way Disney did — but I bet we can figure out a way to do it differently. I have had designer after designer say that we’re the best regional theatre shop to work with because of our quality, our attention to detail and our willingness to collaborate.”

“The story was that the characters got this apartment on a deal,” explains Bishop. “And it needed to be renovated, so they did the basics. When they moved in, they painted everything a neutral color and had the floors done. And then they replaced the appliances. But the cabinetry still is from the ‘70s because they didn’t want to spend the extra money since they’re planning on raising children.”

This attention to detail and specificity is a hallmark of the designs seen on the Playhouse stages. Bishop and her team rely on the designers to give this type of direction — a “feel for the space,” as she calls it.

“As a set designer, you’re creating an environment, and an environment doesn’t stop with the table that you choose,” she says. “How did they get this table? Was it an heirloom? A thrift store find? Those details reflect the owners of the space and will affect the audience’s perception, as well as assist the actors’ performance.”

Marion Williams — a New York-based scenic and costume designer whose credits span the globe — is one of Bishop’s favorite visiting designers to work with.

“I love her vision,” Bishop explains. “I like her aesthetic. She often gets quoted saying, ‘I build fake houses for people who don’t exist.’ And I would say, ‘I create artificial environments for stories to be told.’ It’s a joy to work with people who are still having fun doing the work.”

When Williams designed the Playhouse’s world premiere production of The Revolutionists, she wanted the stage to express the opulence of the Louis the Sixteenth era and the life of Marie Antoinette. She designed a high-gloss parquet black floor and a wall that had extravagant molding detail and doors. In the middle of the stage, Williams elevated the floor and added a larger-than-life, shiny black chandelier.

“The whole vision for what was happening was unique,” Bishop continues. “You’re never going to find this anywhere but in a stage production — and we love a good challenge.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=d4be6280_0)

Any time you visit the Playhouse Scene Shop, you’ll find that they’re building multiple sets at a time. They start the construction process well in advance of each production to ensure that the seamless transition from one set to another stays on schedule. When there are issues with a load-in or with the building of a set, the timelines can’t change. The show must go on, which means the sets must be completed and delivered to the theatre on schedule. Changes or delays with the building or design process can also affect the schedules of the upcoming shows, and the Scene Shop staff must work together with the show’s designers to solve problems on the fly and prioritize them. This ability to solve problems quickly is possible because of our knowledgeable team of local craftsmen.

“Having the people who are building these environments be local gives us a control of fit and finish,” explains Bishop. “No matter what creative challenges are brought our way, what hits the Playhouse stage is always consistent and of the highest caliber because it’s built by a team of craftsmen and artists who know how to work together and truly understand our spaces.”

“You can almost feel the dank air and inhospitable breezes flowing through it,” commented Enquirer reviewer David Lyman. He also emphasized how the “admirable grittiness” of the set flowed right off the stage and onto the actors’ costumes, which were designed by Kathleen Geldard. His words highlighted the power that design can have over an audiences’ perception of the characters onstage and the reality in which they reside. “There is nothing prettified about these people or the world they inhabit,” Lyman concluded.

The Dream Team

Integral to this process is Director of Scenic Production Veronica Bishop, who oversees a team of more than 15 local, union artisans, engineers and craftsmen who work full-time all season long, sometimes alongside extra over-hire staff when more hands are needed on deck. Among the team are carpenters, swings, assistant scenic artists and properties assistants, as well as Technical Director D.W. Jones, Assistant Technical Director Haley Schutzenberger, Charge Scenic Artist Kenton Brett and Properties Manager Liz Lyons. Bishop is among the few women across the country who now run a professional regional theatre scene shop.

who oversees a team of more than 15 local, union artisans, engineers and craftsmen who work full-time all season long, sometimes alongside extra over-hire staff when more hands are needed on deck. Among the team are carpenters, swings, assistant scenic artists and properties assistants, as well as Technical Director D.W. Jones, Assistant Technical Director Haley Schutzenberger, Charge Scenic Artist Kenton Brett and Properties Manager Liz Lyons. Bishop is among the few women across the country who now run a professional regional theatre scene shop. “When you buy a ticket or contribute to the Playhouse, you are supporting local artisans and local employment, because the artists who build, the stage managers who stage manage and the technicians who run the show and create the sound are all residents of the Greater Cincinnati area,” Bishop explains. “There’s a lot of investment for the folks here at Playhouse in our product because we’re making it for our community, for our neighbors. There’s a lot of pride.”

Members of the Playhouse Scene Shop team working on set pieces for the 2016 world premiere of Native Gardens and loading the set into the Robert S. Marx Theatre.

This season alone, the Playhouse Scene Shop will build sets that range from an isolated cabin in Colorado to a regency manor in England; from a tiny house-in-progress in Oregon to a restaurant in 1969 Pittsburgh; and even the animated world of Charlie Brown and the Peanuts gang. To accomplish this annual feat of building 14 unique, high-quality sets — 11 mainstage productions and three Off the Hill touring plays — they’ll team up with nationally recognized designers who have international and award-winning credits to their names.

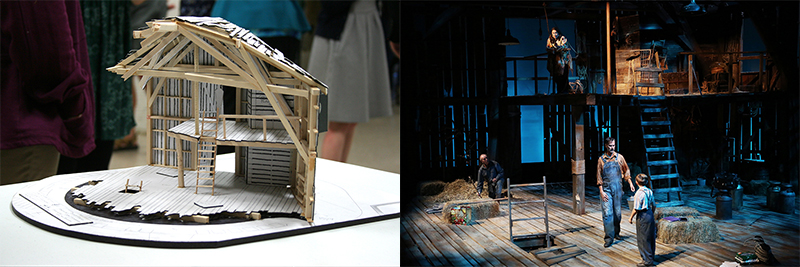

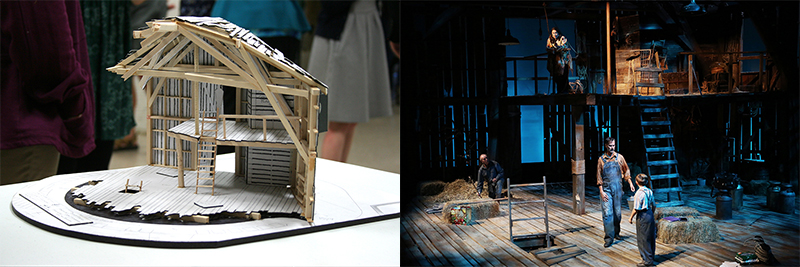

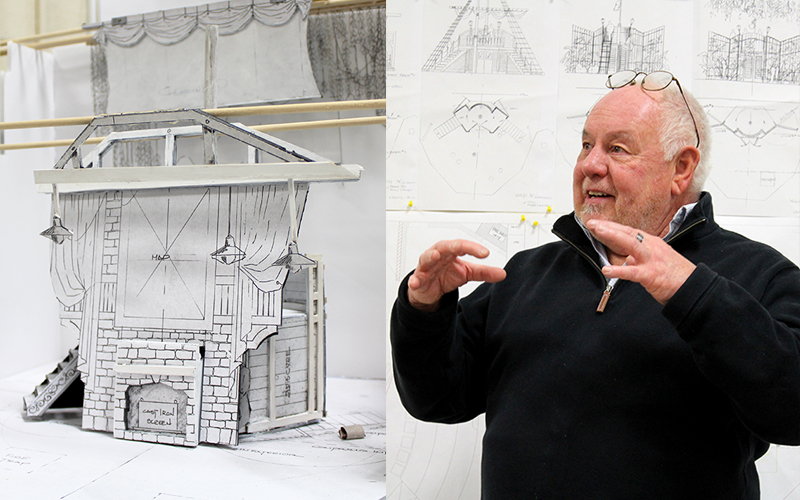

Treasure Island Set Designer Jeffrey Modereger and his set model for the production. Modereger also designed the Playhouse production of Mad River Rising.

“They bring a wonderful, diverse tapestry of ideas and lessons from all the other theatres across the country where they work,” explains Bishop. “We’re hiring designers from Chicago, New York and California who work for other theatres and in television, film, cruise ships and amusement parks. The gentleman who designed A Christmas Carol — James Leonard Joy — has designed extensively for Broadway and the Walt Disney World Company. That’s invaluable. To have somebody come from a place like Disney with great ideas for the Playhouse stage spurs us to collaborate and come up with different solutions to problems that we would normally solve in a standard way. We can’t afford to do it the way Disney did — but I bet we can figure out a way to do it differently. I have had designer after designer say that we’re the best regional theatre shop to work with because of our quality, our attention to detail and our willingness to collaborate.”

The Scene Shop staff and crew rebuild the set of A Christmas Carol on the Robert S. Marx Theatre stage in just four days each season.

The Art of Design

For each production, the set, costume, lighting and sound designers must interpret the script and find the story that their area of the show must tell. For example, the Playhouse’s 2016 production of Mothers and Sons was set in a high-end apartment in an expensive neighborhood of New York City. Set Designer Junghyun Georgia Lee based her designs in the reality of the Manhattan neighborhood she lived in, but she brought insight to the space by adding more to the background narrative of the characters’ home.“The story was that the characters got this apartment on a deal,” explains Bishop. “And it needed to be renovated, so they did the basics. When they moved in, they painted everything a neutral color and had the floors done. And then they replaced the appliances. But the cabinetry still is from the ‘70s because they didn’t want to spend the extra money since they’re planning on raising children.”

Alvin Keith and Stephanie Berry on the set of Mothers and Sons, designed by Junghyun Georgia Lee — who also designed the Playhouse production of Buzzer.

This attention to detail and specificity is a hallmark of the designs seen on the Playhouse stages. Bishop and her team rely on the designers to give this type of direction — a “feel for the space,” as she calls it.

“As a set designer, you’re creating an environment, and an environment doesn’t stop with the table that you choose,” she says. “How did they get this table? Was it an heirloom? A thrift store find? Those details reflect the owners of the space and will affect the audience’s perception, as well as assist the actors’ performance.”

Marion Williams — a New York-based scenic and costume designer whose credits span the globe — is one of Bishop’s favorite visiting designers to work with.

“I love her vision,” Bishop explains. “I like her aesthetic. She often gets quoted saying, ‘I build fake houses for people who don’t exist.’ And I would say, ‘I create artificial environments for stories to be told.’ It’s a joy to work with people who are still having fun doing the work.”

The set model for The Revolutionists, designed by Marion Williams. Jessica Lynn Caroll and Lise Bruneau in The Revolutionists.

When Williams designed the Playhouse’s world premiere production of The Revolutionists, she wanted the stage to express the opulence of the Louis the Sixteenth era and the life of Marie Antoinette. She designed a high-gloss parquet black floor and a wall that had extravagant molding detail and doors. In the middle of the stage, Williams elevated the floor and added a larger-than-life, shiny black chandelier.

“The whole vision for what was happening was unique,” Bishop continues. “You’re never going to find this anywhere but in a stage production — and we love a good challenge.”

How It's Made

The process of creating these background stories and then realizing them onstage is far from easy. From the time Artistic Director Blake Robison selects the scripts for the season all the way through each show’s opening night, the designers and staff are in constant collaboration. Here’s a look at the typical design process:.jpg?sfvrsn=d4be6280_0)

Any time you visit the Playhouse Scene Shop, you’ll find that they’re building multiple sets at a time. They start the construction process well in advance of each production to ensure that the seamless transition from one set to another stays on schedule. When there are issues with a load-in or with the building of a set, the timelines can’t change. The show must go on, which means the sets must be completed and delivered to the theatre on schedule. Changes or delays with the building or design process can also affect the schedules of the upcoming shows, and the Scene Shop staff must work together with the show’s designers to solve problems on the fly and prioritize them. This ability to solve problems quickly is possible because of our knowledgeable team of local craftsmen.

Assistant Scenic Artists Stephen Childress and Stacey Meyer craft and paint set details for Mad River Rising and Misery, respectively.

“Having the people who are building these environments be local gives us a control of fit and finish,” explains Bishop. “No matter what creative challenges are brought our way, what hits the Playhouse stage is always consistent and of the highest caliber because it’s built by a team of craftsmen and artists who know how to work together and truly understand our spaces.”

Unequaled Artistry

The results of this collaboration can create a breathtaking, deceptively realistic and sometimes even overwhelming transformation of the space. Cincinnati reviewers consider the set to be another character in the show, often calling out its significant impact on the production. For example, CityBeat credited “the intricacy of the set, designed by Paul Shortt” as “part of what makes Misery so chilling,” and The Cincinnati Enquirer notably praised the massive, realistic barn built for our 2015 production of Mad River Rising, designed by Jeffrey Modereger.“You can almost feel the dank air and inhospitable breezes flowing through it,” commented Enquirer reviewer David Lyman. He also emphasized how the “admirable grittiness” of the set flowed right off the stage and onto the actors’ costumes, which were designed by Kathleen Geldard. His words highlighted the power that design can have over an audiences’ perception of the characters onstage and the reality in which they reside. “There is nothing prettified about these people or the world they inhabit,” Lyman concluded.