A Part of Tradition

Video games, television shows, operas, ballet, theatre pieces: with hundreds of different versions of the story, A Christmas Carol is the most adapted work in the English language. Published on December 19, 1843, the book was sold out before Christmas day and, thanks to basically nonexistent copyright laws, within weeks there were at least five different theatrical adaptations being staged in Victorian playhouses. Dickens' A Christmas Carol garnered universal acclaim, causing even rival novelist William Thackeray (of Vanity Fair fame) to heap praise upon the piece. Since that fateful publishing day 180 years ago, the story of Ebenezer Scrooge has proliferated holiday culture in many different forms and versions.

What was your first experience of A Christmas Carol? For many, Dickens' original text is not the first point of entry into this perennial tale. Perhaps you're of a generation that remembers Lionel Barrymore reading the novella each year. Or Eleanor Roosevelt. Maybe your toe was a-tappin' to Ralph Vaughan Williams' score for a Carol ballet. Your favorite Scrooge might be Albert Finney. Or George C. Scott. Or maybe it's Vanessa Williams from A Diva's Christmas Carol, Michael Caine inThe Muppet Christmas Carol, Bill Murray from Scrooged, Scrooge McDuck, Mr. Magoo, or Margaret Atwood's Scrooge Nouveau.

Perhaps your first (or favorite) Carol emphasizes the stark divide between the wealthy and the impoverished. Or the theme surrounds our impact on the planet and the importance of taking care of it. Maybe your first Scrooge was meant to illustrate the significance of mental health awareness or serve as a reminder that collective action and support can bring about positive change. There's a Carol and a Scrooge for every sensibility and oftentimes, the adaptation reflects the culture and sensibilities of the time and place in which it is generated, each retelling offering a point of view that is specific and new.

Andrew May as Scrooge. Photo by Tony Arrasmith/Arrasmith & Associates.

Since 1991, Cincinnati audiences have been coming to the Playhouse for their local iteration of A Christmas Carol. It's become a holiday favorite. Some folks from the region boast our Howard Dallin adaptation as their first introduction to the classic story. Their first Ebenezer Scrooge was Yusef Bulos (1991), Alan Mixon (1992 to 1996), Joneal Joplin (1997 to 2004) or Bruce Cromer (2005 to 2021). Regardless of when you first encountered this Dickensian mainstay, A Christmas Carol has become a beloved holiday tradition for many families, reminding them about the many lessons of the holiday season. While the themes of redemption, generosity, and the spirit of Christmas are timeless, new Carols ensure that these themes remain relevant, relatable, and impactful to new audiences and new generations.

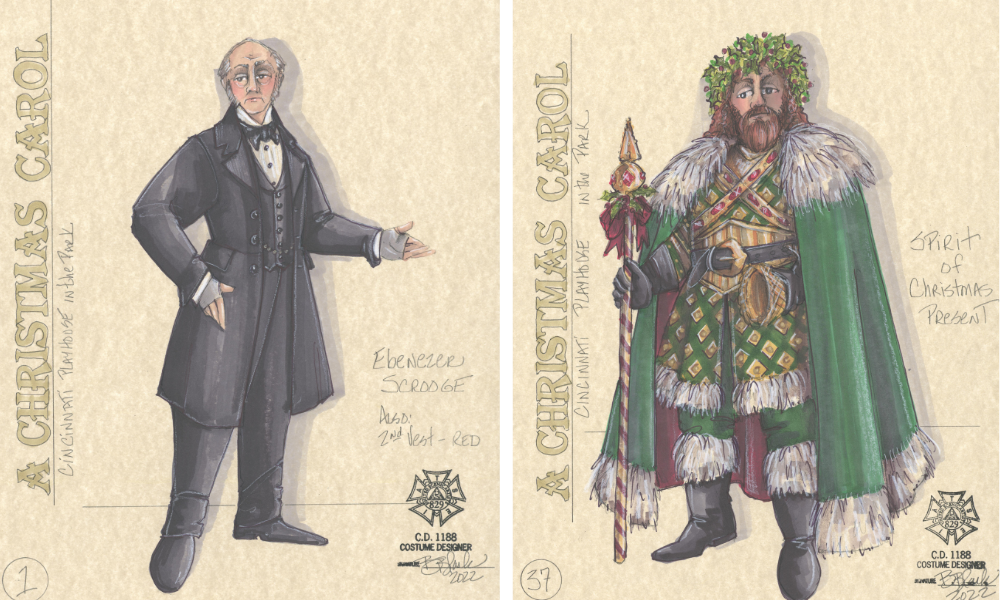

This season, the Playhouse is engaging in this age-old tradition of presenting a new Carol. The script is new; the director is new; the Scrooge is new; the theatre is new. In the brand new, state-of-the-art Moe and Jack's Place — The Rouse Theatre, special effects and theatrical staging can now be executed that were not possible in the old facility. Scenery can fly in and out and audiences are closer to the action. Bruce Cromer, who played Bob Cratchit and then Ebenezer Scrooge, has retired from his 16-year tenure as the legendary miser. Taking up the mantle of this role is Andrew May, who audiences will remember as Hercule Poirot from last season's Murder on the Orient Express. This new adaptation is written and directed by Playhouse Osborn Family Producing Artistic Director, Blake Robison. He began writing the script over a year ago, committed to writing a faithful adaptation that remains and becomes a part of audiences' holiday traditions.

Blake Robison

Blake sat down with us to talk about the Playhouse's new Carol.

For you, what is A Christmas Carol about?

I think it's about redemption, and the joy of the season, and finding peace and purpose in the service of others. That's my answer. I think Dickens' answer is in Fred's speech in the first counting house scene.

There are many things from which I might have derived good, by which I have not profited, I dare say, Christmas among them. I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time as a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they were fellow-passengers on life's great journey, and not another race of creatures to look down upon. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!

I think that's Dickens' answer right there.

What excites you about this story?

I. Love. A Christmas Carol. There are a lot of theatre people who roll their eyes or feel like it's a thing that they have to do every year as part of their season. But, I love seeing so many families of multiple generations come to the theatre together. You have grandparents, parents and kids all attending. I think it centers us as a community. It reminds us of what's important in life. It's this wonderful parable about a person who is at odds with all the humanity around him. He has carved out a life of loneliness and defensiveness. He's put his walls around himself. Then, he has a chance to make amends and reconnect with the world. A timeless message, to be sure, but perhaps an especially timely message for our current social environment.

What did this adaptation process look like for you?

You know, I've seen a lot of A Christmas Carols at many different theatres, not just the one that the Playhouse has done for so many years. And I hadn't gone back and read the novella in a very long time. So, of course, I started there. The idea was not to take Howard Dallin's version and nip and tuck it. It was to go back to the source material and start fresh. Obviously, the story is still the story. The characters are there. Much of the dialogue is the same, because nearly every adaptation of A Christmas Carol starts with Dickens. The lines that you remember, the famous lines, the ones that you look forward to as an audience member, exist in almost every adaptation because they come straight from Dickens. And that is certainly the case here.

That said, every adaptation has some variances that reflect the taste and interest of the adapter and the director. So, in the version that we are premiering this season at the Playhouse, there are some tiny little scenes, that I think are lovely and meaningful and moving, that were not in the pervious adaptation. They're part of the Dickens novel. They're part of the story, but the previous adapter chose to leave those out for whatever reason.

Another interesting part of the adaptation process is that some of the Dickens novel is written with dialogue, so you're using the dialogue that Dickens himself imagined would come out of these character's mouths. And in other scenes, Dickens simply describes the action. So as the adapter, you have to create the dialogue. A good example of that is the Cratchit scene. When we first meet the Cratchit family, they're having Christmas dinner. If you go back to the Dickens novel and read that, there's very little actual dialogue. Mostly, it's in novel form; he's describing things without assigning actual lines to characters. So as an adapter, that's a fun challenge, figuring out how to bring that to life in a theatrical context. We tell stories through dialogue.

What do you hope audiences take away from the production?

Fun. Joy. Family connection and appreciation for the things that make us human. A reminder of the better parts of the human soul and spirit.