A Closer Look at the Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre Remodel

Over the summer, the Playhouse underwent the first phase of its capital construction project with renovations to the newly renamed Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre. The focus of the project was installing more comfortable seats with extra leg room and more accessibility accommodations. The three-month remodel took place from June to August. Capital Projects Manager Phil Rundle, who has previously served as Playhouse Production Manager for more than 30 years, oversaw the project and offers historical information, project details and additional insight.

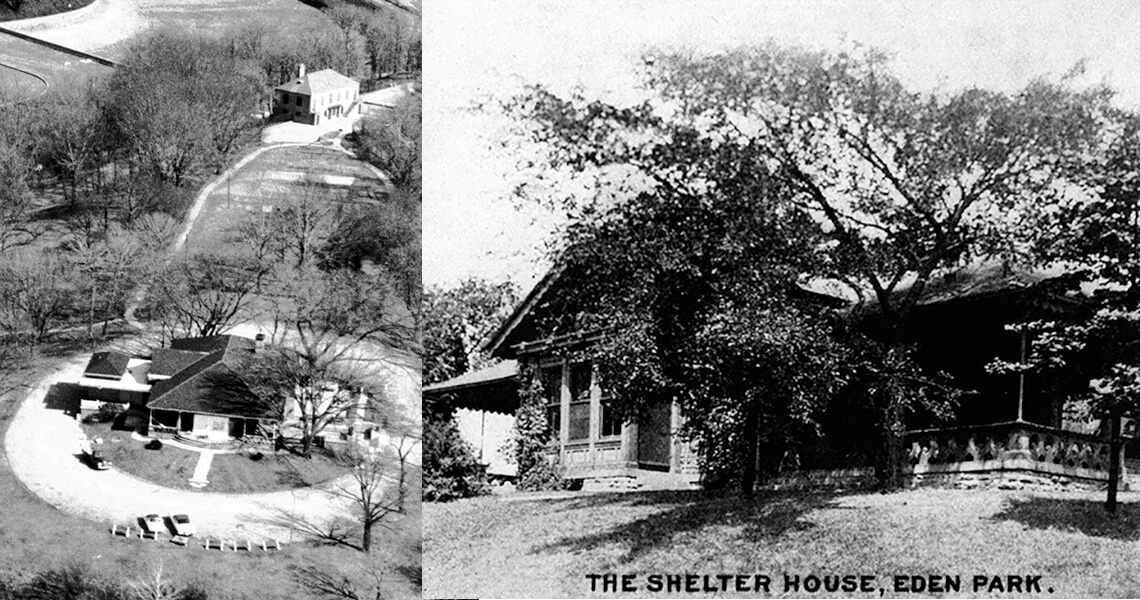

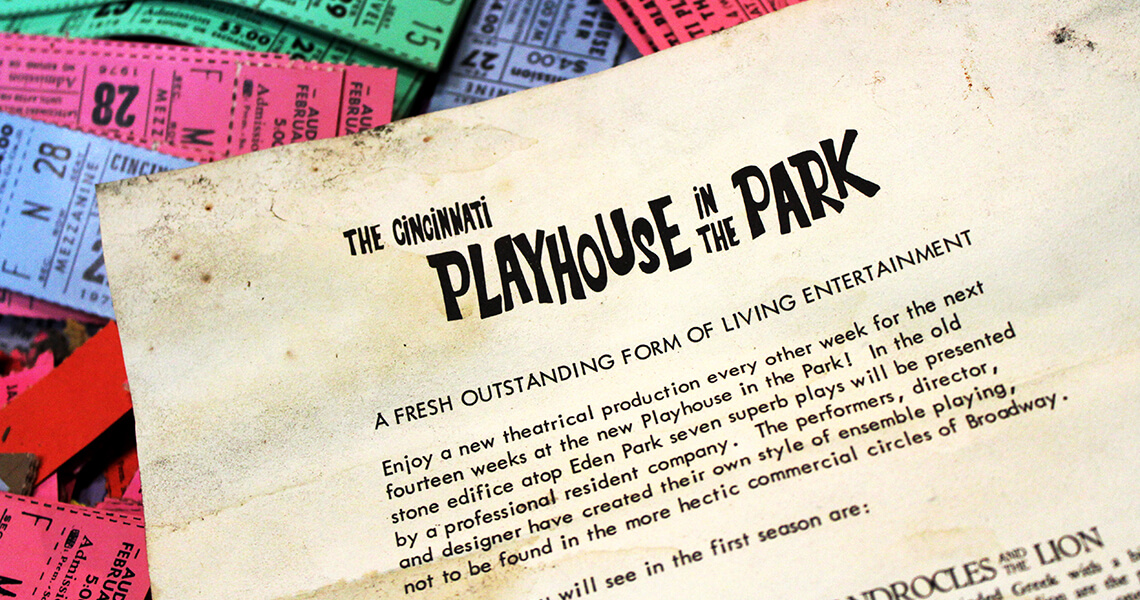

The Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre is steeped in history. It’s where Gerald Covell, then a student from Oberlin College who was inspired by the regional theatre movement that was sweeping across America, realized his dream of creating a Cincinnati theatre company in 1959. When Covell found the 88-year-old shelter house building that overlooked Eden Park, he knew he had stumbled upon the perfect locale. He pounded the pavement for months alongside the theatre’s earliest investors and supporters to remake the shelter house building into a professional performance space. One of those early supporters was Morse Johnson, an attorney with a passion for theatre, who became the Playhouse’s first president. The theatre opened its doors to the public on Oct. 10, 1960, with a production of Meyer Levi’s Compulsion.

Constructing the Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre

The theatre has experienced several different upgrades since its official opening six decades ago. This summer’s remodel focused on taking out the seats and risers that were installed in 1965. The upgraded theatre takes the space down from 225 seats to 172; seven rows have become six. The aisles are wider and, much to the satisfaction of many regular audience members, each seat has more leg room. Altogether, the upgrade keeps pace with current theatre industry standards for patron experience.

Rundle says that over the years, Playhouse staff and board members have considered building an entirely new, small-stage theatre. But ultimately, they decided to maintain the integrity of the original building’s stonework and only make improvements to the theatre space. The windows shown above were windows into men’s and women’s restrooms that existed in the early part of the 20th century and had been removed and covered up throughout different renovations.

When construction began in June, Rundle says they found that the flooring had been raised consistently to the point of being almost a foot higher than the original floor. So, this summer, they stripped the floor down to its original framing and repaired the foundation. This meant that the ramps at the entryways have decreased in steepness. Lowering the floor also meant lowering the stage, which allowed them to increase the steepness of the seating on the sides; the result is greatly improved sightlines for audiences.

Unexpected Finds

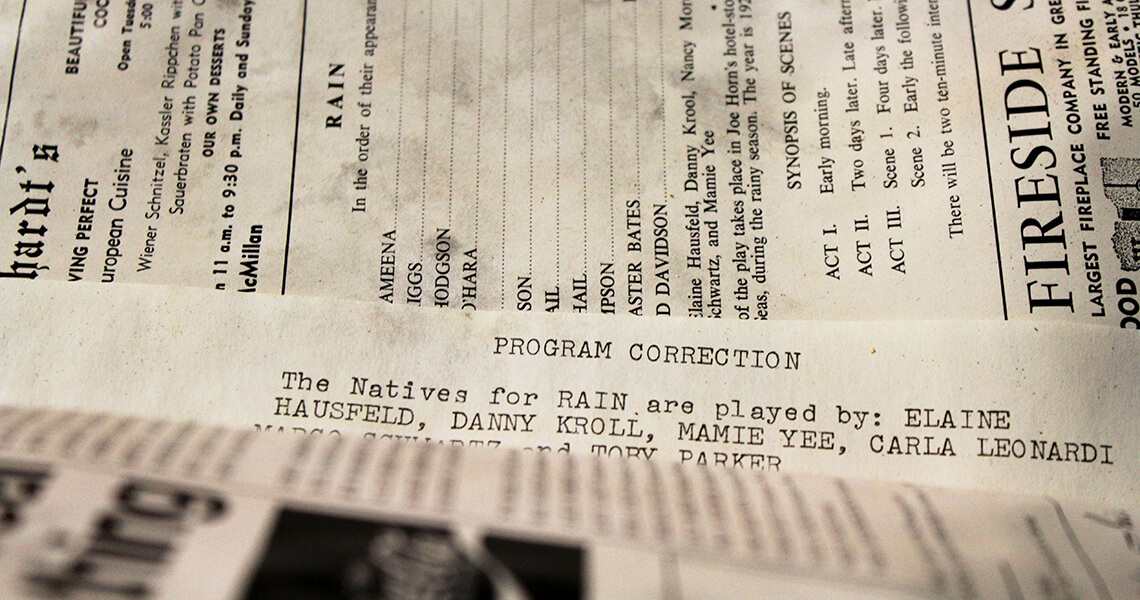

The early stages of construction allowed for some unexpected discoveries. Beneath the risers on the eastern side of the theatre, Rundle uncovered a stockpile of paper documents and items that, most likely, were stored by box office staff a few decades ago because they didn’t have enough space.

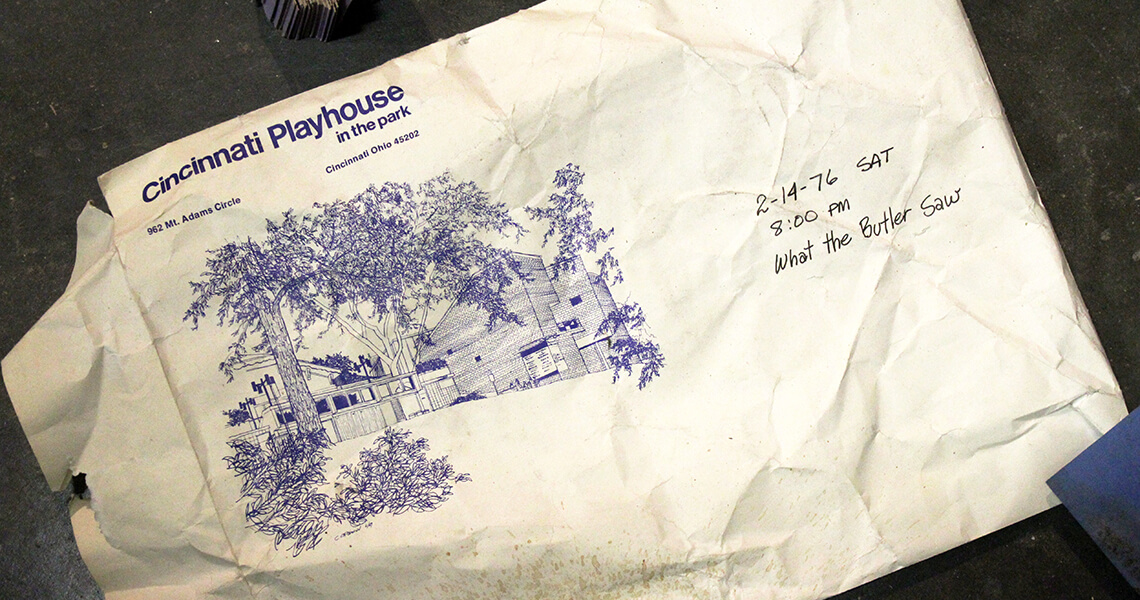

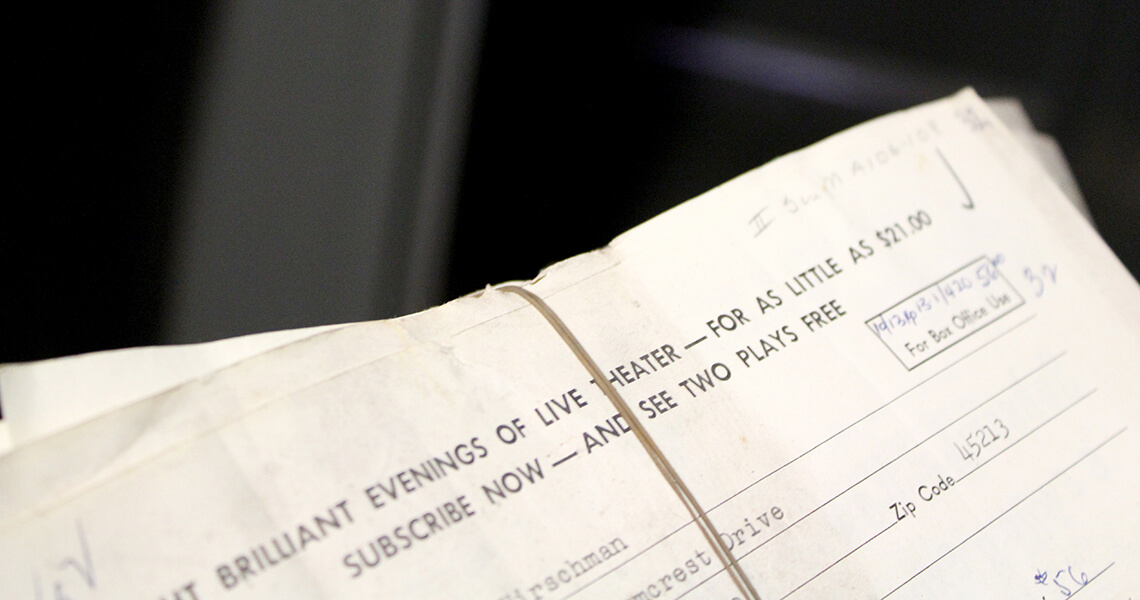

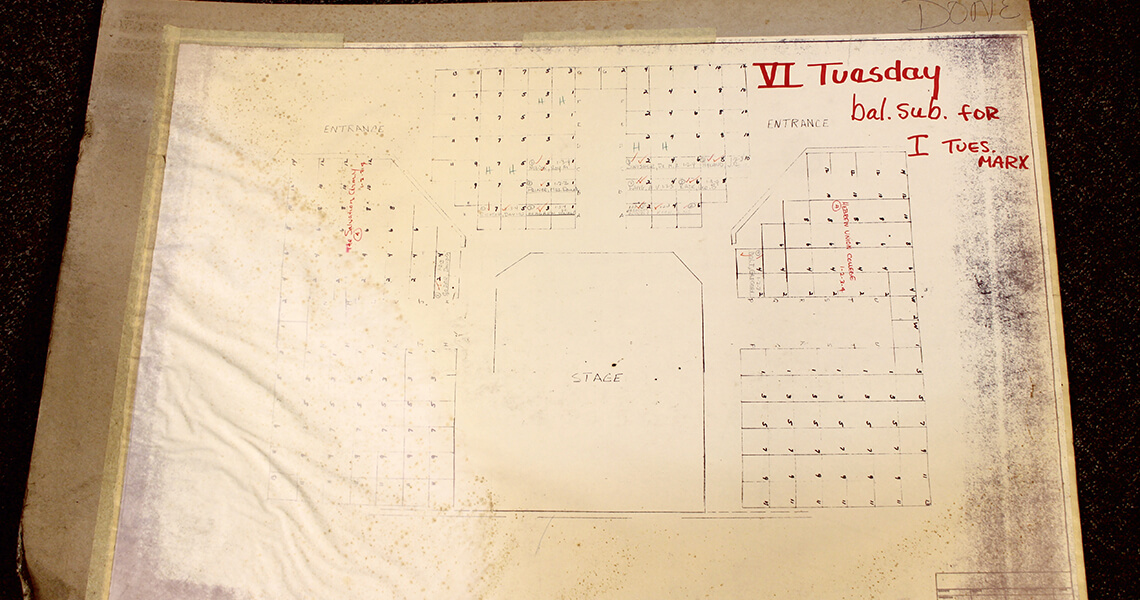

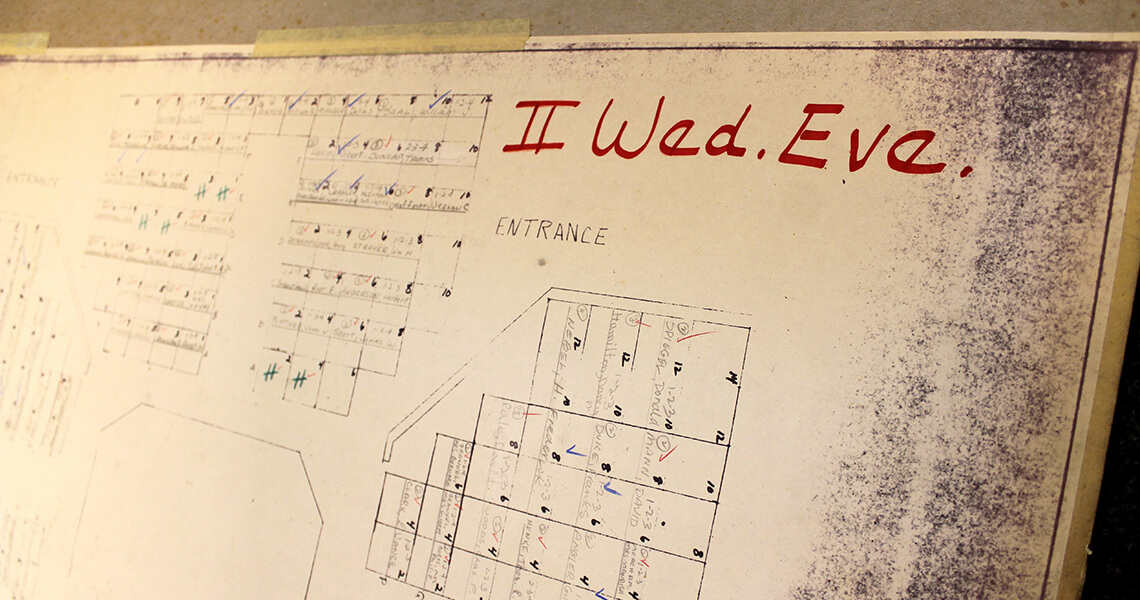

Before the Marx Theatre was built in 1968 and before the lobby was built in 1980 to unite the two theatres under the same roof, the box office had been located on the eastern side of the theatre where the plaza porch is now. Rundle uncovered bags and boxes of unsold tickets, correspondence with subscribers, subscriber ledgers, promotional documents and various day-to-day documents.

During a time Rundle calls “pre-computer,” the box office staff (which was comprised of volunteers for many years in the 1960s) mapped out subscribers’ seats with handwritten charts for every single performance. The first year the theatre was in operation, it had 300 subscribers. Today, the Playhouse maintains a subscriber base of more than 12,000.

The 1969 promotional ad for The Traveling Theatre Troupe was also found in the theatre. It represents the Playhouse’s apprentice academy. Similar to the Bruce E. Coyle Intern Company that was established in 1992, the academy was comprised of young theatre artists who performed children’s shows and late-night improv shows, held various crew positions and assisted production staff.

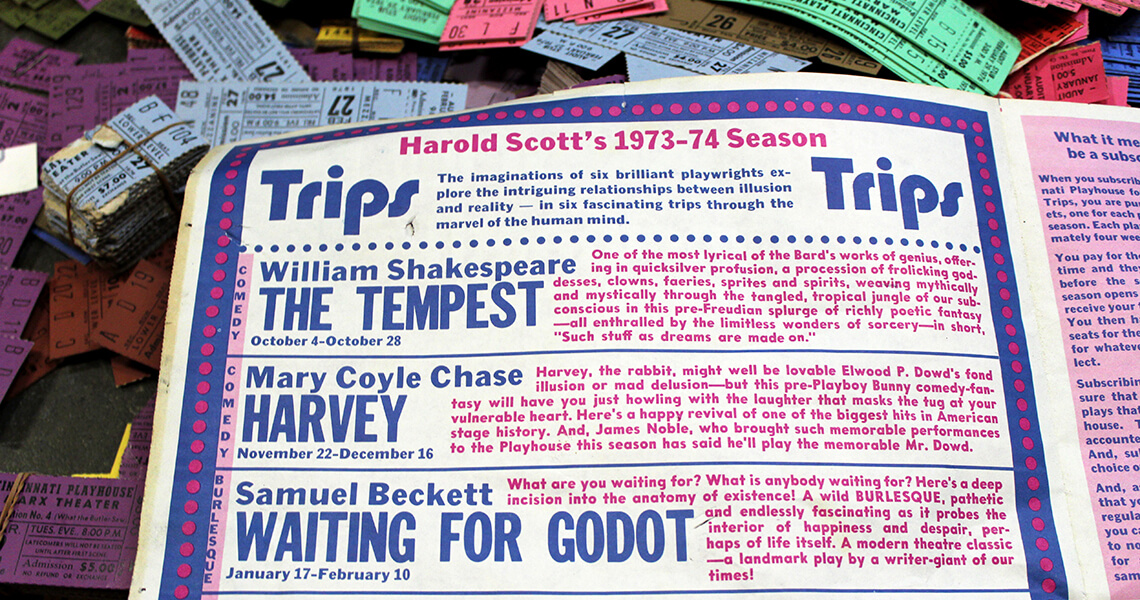

This promotional ad represents Harold “Hal” Scott’s season as artistic director. Scott was the first African-American artistic director of any professional regional theatre. He worked alongside Sara O’Connor, the first female managing director of a regional theatre. Their tenure together featured a classically American theatre season in the Marx and an experimental theatre festival in the Shelterhouse. Their approach prompted an incredible rise in subscriptions, with an increase of 105 percent.

A Theatre for Today

According to Rundle, they painted the brick and the walls a deep black color to give an avant-garde, “black-box theatre” look. The effect of this aesthetic makes the room appear to “go away a little bit more,” pulling the

audience’s focus more deeply to the stage. Altogether, the newly renamed Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre now features brand new seating, refinished flooring, new carpeting and tile work, LED house lighting, reconstructed entryway ramps, and a

hearing loop system which works with existing hearing ads or cochlear implants.

The Rosenthal Shelterhouse Theatre’s exciting changes were made possible by a generous gift from The Rosenthal Family Foundation. The remodel represents the first phase of the theatre’s capital construction project to build a new, mainstage theatre complex in the Playhouse’s iconic, Eden Park setting.