The Feminine Mystique Through Erma Bombeck's Lens

“It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction… Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘is this all?’” – Opening passages of The Feminine Mystique

In 1963, suburban housewives rushed out of their homes to purchase what would quickly become one of the most subversive books of the decade: The Feminine Mystique, written by feminist author and activist Betty Friedan. The nonfiction book examines the “strange stirring” that Friedan found amongst educated, middle-class, suburban housewives of the 1950s and 1960s. It was met with heated responses across the board, from anger and offense to gratitude and validation.

“The suburban housewife,” Friedan writes, “was the dream image of the young American woman and the envy, it was said, of women all over the world.” Now that the men were home from war and back in the workplace amidst a booming economy, these women assumed the responsibilities of supporting their husband and raising their children. They could rely on the promise that they could instead fill their lives with their family’s needs and enjoy the leisure of suburbia.

Friedan found a slew of flaws in that promise of fulfillment.

The “feminine mystique,” by Friedan’s definition, is an unrealistic image of overt femininity: “she was healthy, beautiful, educated, concerned only about her husband, her children and her home. She had found true feminine fulfillment.” This image was romanticized in a society that was returning to traditional values and stability following years of economic depression and global conflict. A stable home life represented a welcome return to normalcy, and that home life needed a reliable female homemaker and productive male breadwinner. If Post-War normalcy was the objective, these traditional gender roles were the vehicle to take it there.

The mystique was perpetuated by advertisers, women’s magazines and television, constantly impressing upon their audience idealistic images of happy housewives. Therein lay the problem, Friedan found. These images didn’t tell the whole story.

Underneath this American family portrait, the suburban housewife in The Feminine Mystique possessed a strong feeling of disappointment. She was educated but had swapped her textbooks for cookbooks, rendering her college degree as little more than a qualifier for marriage. Her fulfillment depended on the fulfillment of others and not her own, and domestic responsibilities had left her feeling devoid of personality identity. Friedan called it “the problem that has no name.”

One year after The Feminine Mystique’s publication, Erma Bombeck began writing her column “At Wit’s End” in her community’s newspaper, and it would later become syndicated in 900 newspapers nationwide. She chronicled domestic life from inside the trenches with wit and wisdom. “Motherhood is the world’s second oldest profession, but unlike the first, there’s no money in it,” she once wrote.

In many ways, Bombeck was the woman described in The Feminine Mystique. She, too, was an educated, middle-class, suburban housewife who seemed to embody the problem that has no name. Similar to the sentiments within Friedan’s book, Bombeck once wrote, “I had been hiding my hopes and dreams in the back of my mind. It was the only safe place in the house.”

She threaded these ideas into a razor-sharp commentary on the unrealistic standards of housewifery. The difference is that while Friedan was politically motivated to awaken women’s anger, Bombeck used her humor as a tool to remind her readers of the absurdity of the expectations placed on them. She validated their frustrations simply by documenting her own.

Through Friedan and Bombeck, we have a greater understanding of “the problem that has no name” and “the feminine mystique.” They reveal the psyche of American women in a time when their role was being redefined with nuance and autonomy. Their works are important hallmarks of history, inviting women to not only explore their own stories and lives but to share them with honesty and purpose.

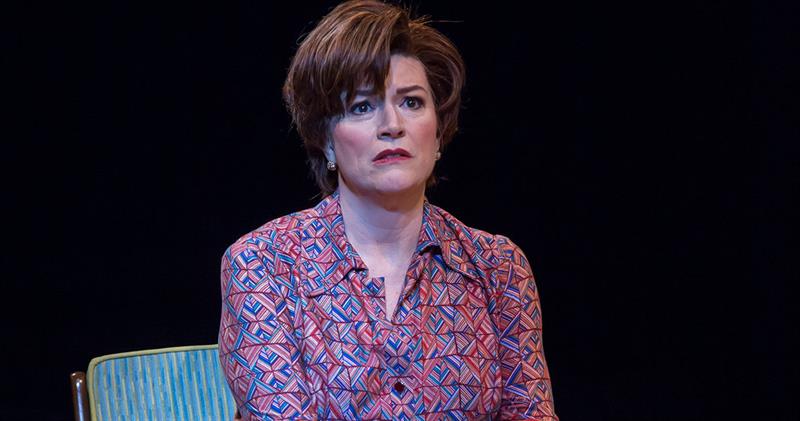

To learn more about the Playhouse production of Erma Bombeck: At Wit's End, visit the production detail page.