Beyond Stereotypes

4a6f5f60-f08d-4c3b-9421-d7c6ed9c5d27.png?sfvrsn=2f337380_3)

The Stereotype of the Perpetual Foreigner

The Chinese Lady, by Lloyd Suh, is based on the true story of Afong Moy, thought to be the first Chinese woman to step foot on U.S. soil in 1834. Suh’s blending of historical accounts and deep exploration of character compellingly parallel Moy’s real-life performances and travels. How much has changed in the almost 200 years since Moy’s arrival? How has the relationship between the U.S. and its Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) citizens changed? One way to dive deeper into these parallels is to look at the historical and ongoing perception of the AAPI community in the United States.

What’s the first thing you think of when talking about the AAPI community? There are numerous stereotypes that have long plagued AAPIs in the United States. One of these stereotypes is that of the “Perpetual Foreigner.” This stereotype casts AAPIs as “other” and “outsider” regardless of

where they were born or how long they have lived in the United States.

f9ac9c2f-09e5-4247-9365-f3ec6f32dd4b.png?Status=Master&sfvrsn=3e367380_3)

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a dramatic rise in anti-Asian attacks and rhetoric. Fears associated with the pandemic may be especially linked to Asians because this particular pathogen emerged in China. Compounded by an American tendency to ignore the distinctions among Asian ethic groups and media coverage of the pandemic also implicating Asians, the general perception of AAPI in the United States is as lacking “Americanness.” This is a perfect example of the “Perpetual Foreigner” stereotype being at play.

- Today, 1 in 3 Asian American and Pacific Islanders were born in the United States, even though immigration from Asia remains significant. In fact, the U.S.-born AAPI population is now growing faster than the AAPI immigrant population.

- 45% of all foreign-born Asian American and Pacific Islanders have lived in the United States for more than 20 years.

Stereotypes and Gender

Harmful stereotypes about Asian women being sexually submissive, feminine, and meek or villainous and deceitful have been supported by both the media and the U. S. government. The first instances of rhetoric that Asian, specifically Chinese, women were “sexually unclean” and “inclined towards prostitution,” occurred around the Page Act. Passed in 1875, the Page Act effectively prohibited the

immigration of East Asian women into the United States. As military presence expanded in Asia, the stereotype of Asian women as prostitutes persisted and was encouraged. In some instances, U.S. forces were running brothels outside of their camps, populated with

local women. In the media, the stereotype of the “Dragon Lady” and further sexualization of Asian women is evident in pieces like The Thief

of Bagdad, Madama Butterfly, Full Metal Jacket, and Kill Bill.

Harmful stereotypes about Asian women being sexually submissive, feminine, and meek or villainous and deceitful have been supported by both the media and the U. S. government. The first instances of rhetoric that Asian, specifically Chinese, women were “sexually unclean” and “inclined towards prostitution,” occurred around the Page Act. Passed in 1875, the Page Act effectively prohibited the

immigration of East Asian women into the United States. As military presence expanded in Asia, the stereotype of Asian women as prostitutes persisted and was encouraged. In some instances, U.S. forces were running brothels outside of their camps, populated with

local women. In the media, the stereotype of the “Dragon Lady” and further sexualization of Asian women is evident in pieces like The Thief

of Bagdad, Madama Butterfly, Full Metal Jacket, and Kill Bill.

The Stereotype of the Monolith

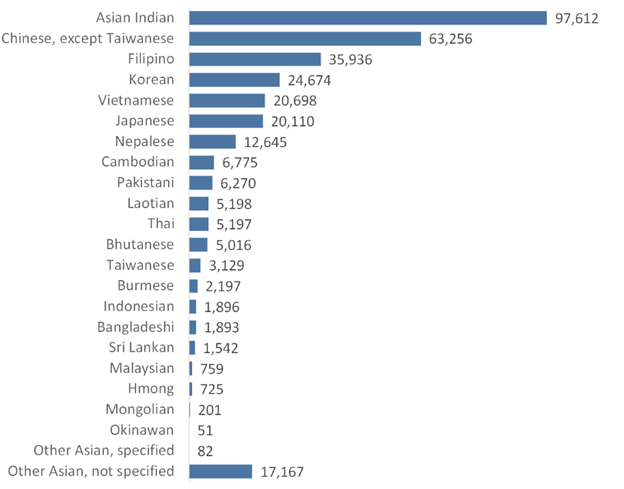

Another harmful stereotype casts all AAPI people as monolithic, meaning they all share the same history and background. However, consisting of more than 50 ethnic groups with different cultures and histories in the United States, the diversity of AAPI heritage and experience is truly too vast to simplify under such a simple stereotype.

Many different Asian ethnicities and backgrounds are represented in the population of Ohio. As shown in the graph, 60% of Asian and

Asian Americans in Ohio are Asian Indian, Chinese, or Filipino.

Thoughts from AAPI Community

“The hypersexualization that I faced, probably as young as [when] I was 6, changes how you

consider sex and sexuality. It made me question what it was like to be desired, and what it

meant beyond being a sex object.”

—

Elim, 26, Georgia

“I think the first word I think of is ‘invisible.’ Aside from stereotypes of Asian women

being very quiet, which I’ve, in my whole life, intentionally fought against, I have been

thinking a lot about social situations where I just don’t have any social capital.” —

Annie, 26, New York City

“To be completely candid, I’m more embracing of being Asian American now that I had been previously. That feeling of being left out, of not belonging, is something that I internalized for a long time.” — Melina, 40, Boston

“Unfortunately for many who have immigrated to the United States this feeling of not belonging can extend beyond the AAPI experience in the United States to interactions with origin cultures. Many are stuck balancing the need to assimilate to American culture for safety with trying to hold onto any cultural connections. Often made more difficult because of the

strategies immigrants adopt for survival in the United States. One example is not being fluent in our own Asian culture’s language due to a high pressure to speak only English and to speak it without an accent. At my international school you were not allowed to speak anything but English on campus, to the point of entire class grades being punished if Korean was spoken too often. Unfortunately, these survival strategies mean that we are alienated from the countries we are being told to “go back to,” resulting in many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders being a perpetual foreigner in both the United States and in any countries they have cultural ties to.”

—

Hahnji Jang, Costume Designer and Cultural Consultant, The Chinese Lady

“I STILL BELIEVE IN OUR CITY” POSTERS BY AMANDA PHINGBODHIPAKKIYA.