The Camera in the Theatre: Staging a Show for Film

Each season, the Playhouse produces educational touring shows that are performed at schools for students and at community centers around the region for families. We had originally planned to open the 2020-21 educational season with an adaptation of The Wind in the Willows. When the COVID-19 pandemic impacted our programming decisions, our production and education departments had to creatively problem-solve a way to keep students and families engaged with theatre. We decided to still produce The Wind in the Willows for the fall, and in place of live performances, we provided a professionally filmed, multi-camera recording of the production.

We collaborated with long-time, Cincinnati-based partner Optic Lizard, whose work can be seen in our promotional photo and video content for mainstage shows. This video team

included Tony Arrasmith, Joe Harrison and Todd Joyce. Together, we produced a virtual performance of The Wind in the Willows designed specifically to adhere to pandemic-related protocols and to stream from home. Here’s how we did it.

Pre-Production

One of the first steps in bringing The Wind in the Willows to life included a meeting of the creative minds to bridge the gap between the worlds of theatre and video. Filming a live theatrical performance isn’t nearly as simple as placing a few cameras in front of the stage and pressing record. What’s more, health and safety guidelines set by the City of Cincinnati, the State of Ohio and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posed new logistical hurdles to clear in order to perform and film.

The Optic Lizard video team held meetings with the Playhouse team and The Wind in the Willows designers to consider the technical and logistical differences:

• Would the actors wear body mics, or would they be recorded by a boom operator?

• What impact do face masks make on actors’ mics, and how would they sound on camera?

• How does theatrical stage lighting look through a 4K camera lens, and

would the video team need to bring in special lighting equipment?

• Would the production be staged on a scene-by-scene basis with differing production elements, or would they perform straight-through like a traditional live performance?

Each of these questions, and more, were discussed at length prior to rehearsal.

Rehearsals

The Wind in the Willows Director Daunielle Rasmussen worked with her team in the education and community engagement department to equip themselves with practices and protocols that would ensure actor and staff safety. These included:

• Providing breathable rehearsal masks that accommodated actor movement and physicality;

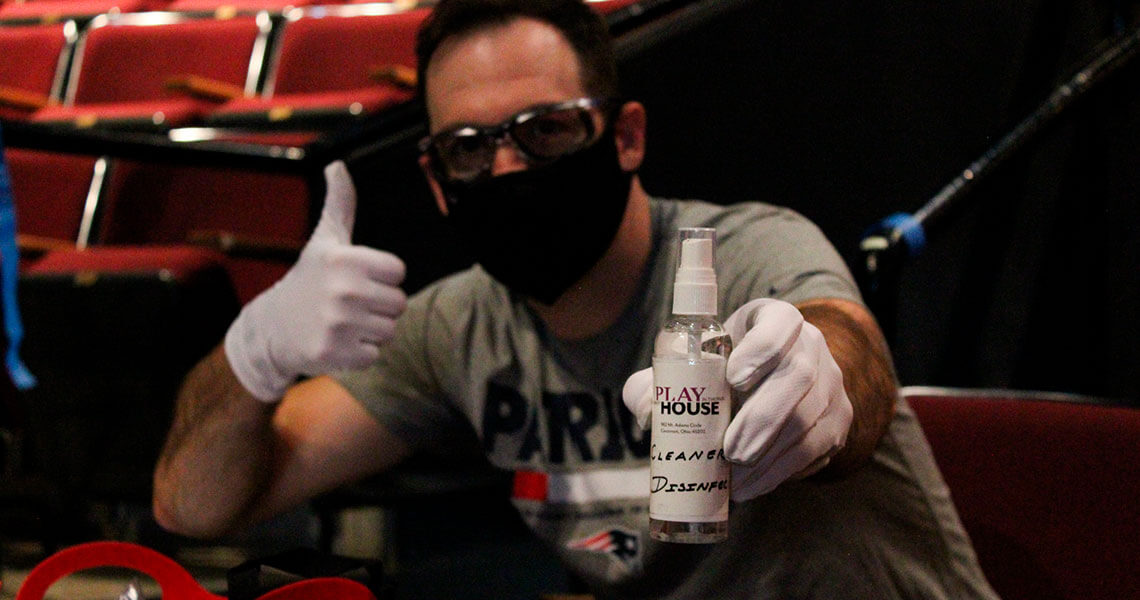

• Stocking up on sanitizer and disinfectant spray to wipe down props and scenery between rehearsal runs;

• Taping a grid of six-foot square boxes onstage to keep social distancing in mind while blocking scenes and rehearsing;

• Identifying two different groups, or “pods,” who would be in proximity together throughout the rehearsal process in order to minimize group contact and reduce possible spread;

• Performing routine health assessments, including daily symptom checks and weekly testing for COVID-19;

• Designating individual, offstage areas for each actor so that they had their own space to be in during breaks;

• Providing individual hospitality stations (which had essentials like tissues, hand sanitizer and cough drops) for performers and production team members.

Costume Designer Melanie Mortimore worked with the production team to create a wardrobe that included face masks and gloves for the performers to wear. The story’s characters (Ratty, Mole, Badger, Toad and other woodland animals) prompted Mortimore

to make artistic use of the face-mask requirement. She opted for cloth masks that were painted with neutral expressions. Says Mortimore, “In some ways, this is like traditional mask work in theatre, where the actor must then embody physical

movements to express emotion often recognized through facial expression.” Actors wore gloves that were dyed neutral to their characters’ costumes, and each performer had a stylized hat that helped them further embody their characters.

The production and video teams chose to use body mics, which wrapped around the back of the actors’ heads and lay against their cheeks. The inclusion of the face masks helped minimize the visual of the mics as they were worn. One wardrobe item that

Mortimore considered was a pair of goggles for each character, but they decided not to include them once they realized they blocked the actors’ visual access and made it more difficult to read the actors’ expressions.

Filming

One of the key differences between performing a theatrical production and filming for the camera is what the viewer sees at any given moment. In theatre, all the action takes place onstage where lighting, movement, scenery, props, sound, music and performance all come together at once so that the story is told in real time. In film, the camera takes on the perspective of the viewer from a variety of distances, giving the opportunity to get either close to or far from select moments and details. Filming The Wind in the Willows called for theatre and film to meet in the middle.

With insight from the production team on how to navigate the theatre space and make the most of the technical facilities available, the video team prepared a shot plan and filming strategy. They would use four cameras, each with a different angle of and

distance from the stage. This approach allowed for a variety of options to work with during post-production. Two cameras captured stationary static shots with a straight-forward view of the stage. The other two cameras followed the action on either

side of the stage from an angle to capture moments in close-up. Shooting close from these two angles had a visual effect that appeared to minimize the distance between characters onstage.

The video team attended the dress rehearsal the day before filming, which allowed them to finalize their camera placement, lighting and audio-recording approach. As the cast rehearsed onstage, they filmed test shots. This gave Rasmussen insight into how

the cameras were recording the action and allowed her to make any necessary adjustments before filming the final performance.

The video and production teams agreed that cameras would favor wider shots and medium shots as well as a few close-up shots that highlighted some performance details. This would allow the viewing experience to feel as familiar as seeing it live.

The lighting approach followed suit. Since educational shows tour schools and community centers, they often work with the lighting that’s available onsite. This is largely different from mainstage lighting, which often calls for dramatization and

style. To stay faithful to how students and families would ordinarily experience this show, the video and production teams opted for a standard lighting approach that stayed consistent throughout the play. Playhouse Electrician John Parr assisted

in capturing the optimal lighting set-up so that the camera didn’t pick up any major contrasts or shadows that would pull the viewer out of the moment. The Playhouse provided all the lighting equipment, and the video team did not need to bring

in any additions.

The video and production teams worked in tandem to record sound. The actors’ body mics were recorded and managed by Playhouse Audio Engineer M. Adam Jacob in the Marx Theatre sound booth. The video team also placed a shotgun mic in the front of

the stage to record ambient sounds like footsteps and door knocks — small details that go a long way in bringing the story to life. At the end of filming, Jacob sent the full audio file of the actors’ mics to the video team to use for

assembling a cut of the production.

Post-Production

Using FinalCut editing software, the video team synced up the footage from the four cameras, the shotgun mic and the sound booth audio file. The variety of shots allowed for an abundance of choices that would make the show more dynamic. The wide and medium

static shots served as a visual baseline for the show, and the close-up shots from different angles provided a way to get closer to the characters and capture key details of their costumes, facial expressions, movements and performance choices. The

video team worked closely with the Playhouse team to gather feedback throughout the editing process.

When the video team had a visual cut of the video, they sent the file to Sound Designer Trey Tatum, who had created a musical score to accompany the story. He added comical sound effects (like an exaggerated sound of a crank that started one of the character’s

cars) and added details like bird chirps and moving water to fully round out the soundscape. Once the video was complete with Tatum’s audio additions, the video team sent the final version to the marketing department for upload and release.

You can view The Wind in the Willows until Nov. 8. Learn more about the show on our production detail page.