The Evolution of African American Gospel Music

Marie and Rosetta tells the captivating life stories of gospel singer Sister Rosetta Tharpe and her young protégée Marie Knight. Set in Mississippi in 1946, the play with music chronicles the singers’ first rehearsal before setting out on tour. Sister Rosetta was already on her way to becoming a legend for her trademark fusion of traditional gospel with secular rhythm and blues. Knight brought a “high church” sound reminiscent of classic spirituals. Their signature collaboration reflects the evolution of African American gospel music, from its roots in spirituals to the rock and roll we know today.

Chaz Hodges as Marie Knight and Miche Braden as Sister Rosetta Tharpe in Marie and Rosetta; photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Spirituals

The true roots of African American gospel music lie in the American South of the 19th century. Spirituals emerged when slaves held informal gatherings together and improvised folk songs. With echoes of biblical stories and the teachings of Jesus Christ, spirituals told the harrowing story of American slavery with call-and-response counterpoint and freeform rhythm. Songs such as “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and “Rock My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham” offer personal accounts of the slave’s struggle with freedom, identity, heritage and spirituality.

Regarded by scholars as the most significant form of American folk music, spirituals combined musical elements of African culture with the lived realities of enslaved peoples in America.

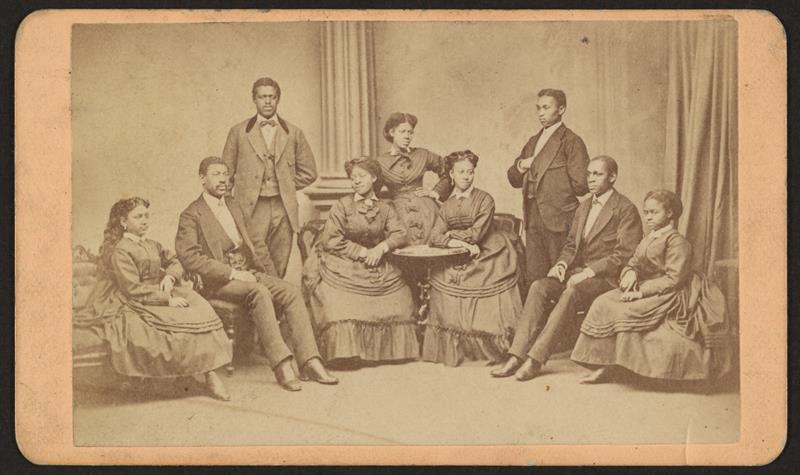

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, pictured here between 1870 and 1880, were among the first vocalists to introduce the music of spirituals to the rest of society and culture in the 1870s, thus preserving the legacy of the musical tradition. Jubilee Singers, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn. Source.

African American Churches

African American gospel music saw a dramatic shift in the late 19th century following the abolishment of slavery, due in large part to the rise of free and open Christian churches that served black congregations. Spirituals took on new musical forms and developed more energetic, up-tempo sounds — early notes of rhythm and blues. The call-and-response form of early gatherings led by impassioned preachers soon became standard.

Pentecostal churches, in particular, embraced music as integral to their expression of faith. They adopted the belief of The Bible’s Psalm 150: “Let everything that breathes praise the Lord.” Choirs introduced organs, tambourines and string and brass instruments into their services, and music was woven directly into preachers’ sermons. Beginning in the 1920s, services were recorded and distributed, which helped spread gospel to the masses, including white audiences.

"Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," performed by Fisk Jubilee Singers between 1915 and 1920. Written by Wallace Willis; recorded by the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Music album Fisk Jubilee Singers Vol. 2 (1915-1920). Source.

Chicago Gospel

As African Americans migrated from rural southern towns to northern urban cities, their musical stylings and forms of worship followed. Chicago became an epicenter for gospel music shortly after the turn of the century. Gospel artists and composers collaborated with secular musicians who played piano, guitar and brass instruments. Thomas A. Dorsey, the son of a southern Baptist preacher and now considered the father of gospel music, pioneered the sound by blending spirituals and traditional worship music with blues, jazz and swing.

Dorsey, along with fellow gospel artist Theodore Frye, organized the first modern gospel chorus at Ebenezer Baptist Church. They then launched the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses. Performers included Mahalia Jackson, Roberta Martin and even Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Each of them became immensely popular artists in the region as a result. Chicago also became home to nearly a dozen gospel music publishing houses. Classic gospel tracks that have seen countless recordings and were originated in Chicago include “Peace in the Valley” and “Take My Hand, Precious Lord.”

Mahalia Jackson, 16 April. 1962. Carl Van Vechten - Van Vechten Collection at Library of Congress.

Rhythm & Blues and Rock ‘n’ Roll

Alongside gospel’s rise in popularity was the emergence of rhythm and blues (R&B). Much like Chicago gospel’s sound, R&B reflects the migration of African Americans to northern cities and their influence on each other’s music. The genre, which was largely formed in the 1940s, includes sounds of boogie woogie, swing, jazz and blues. Despite its predominantly secular nature, early R&B artists drew inspiration from African American gospel music in their form, styling and performance.

The genre not only reflects a quickly growing musical culture but also a changing, post-World War II America. The issue of segregation was growing in awareness and legislative action, and R&B followed suit. The name itself was controversial: “R&B” was a general marketing term that denoted “African American music,” and it was created to replace the term “race records.” These efforts were done to appeal more strategically to white audiences. As racial divides intensified around the country, R&B music found a broad, cross-cultural appeal with young listeners who would amplify the significance of the music to audiences at large and, ultimately, society.

These social and artistic forces combined to create the foundation of rock and roll, embodied by a single performer: Elvis Presley. His 1954 hit single “That’s All Right,” recorded at Sun Records by Sam Phillips, officially established the genre that changed the face of music. He (along with rock pioneers Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard and Chuck Berry) list the music of Sister Rosetta as one of their most important influences.

To learn more about the Playhouse’s production of Marie and Rosetta, presented by Leading Ladies, visit our production detail page.