Broadway: The Stages that Made the Marx Brothers Famous

Dec 5, 2017

By the 1920s, the Marx Brothers had been touring their musical comedy acts steadily throughout the country. They had morphed from The Four Nightingales to Marx & Gordini to The Six Mascots, and performed in productions of Fun in Hi Skule (1910) and On the Mezzanine Floor (1921), amongst others. They had run the gamut of vaudeville success and failure. Yet the world of theatre was on the cusp of change. New York City had become a bustling theatre town that would soon launch the Marx Brothers into stardom.

The mid-1800s saw a major shift in entertainment in New York. Vaudeville had yet to become a bonified art form, and theatre was divided evenly between the upper and lower classes. North of downtown Manhattan had been farmland, but in 1836, Mayor Cornelius Van Wyck encouraged New Yorkers to migrate further uptown to escape the crowded downtown streets and to enjoy the “clean air.” This move initiated the urban development of the city, and the region became the foundation of what is now the Theater District.

.jpg?sfvrsn=afde6080_0&MaxWidth=225&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=A6A17A01CAC0D75B4258B97B7FDB01A3B3AC371E) Early Broadway heavyweights like Oscar Hammerstein were among the first to create the district. Hammerstein built two theatres in the region, and by 1900, the number of theatres on Broadway had increased to 20. Now historic buildings such as the Lyceum Theatre and the New Amsterdam Theatre (which are still in operation) were built in this time period and helped foster the growth of the city’s performing arts. Vaudeville filled the stages, and soon a newly popular performance style would emerge in the revue — a similar form of song and dance variety that featured glitzy, comical and sometimes scandalous performers. With its emphasis on music, the revue offered entrée for such legendary musicians as Ira and George Gershwin, and Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart of Rogers and Hart.

Early Broadway heavyweights like Oscar Hammerstein were among the first to create the district. Hammerstein built two theatres in the region, and by 1900, the number of theatres on Broadway had increased to 20. Now historic buildings such as the Lyceum Theatre and the New Amsterdam Theatre (which are still in operation) were built in this time period and helped foster the growth of the city’s performing arts. Vaudeville filled the stages, and soon a newly popular performance style would emerge in the revue — a similar form of song and dance variety that featured glitzy, comical and sometimes scandalous performers. With its emphasis on music, the revue offered entrée for such legendary musicians as Ira and George Gershwin, and Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart of Rogers and Hart.

At the turn of the century, brothers Sam, Lee and Jacob Shubert began to acquire several different theatres and produce successful and popular shows. They were highly instrumental in creating noteworthy buzz that elevated Broadway’s reputation. In addition, they bought and operated theatres across the country. By the mid-1920s, they had owned, managed or booked more than a thousand houses in the nation. The Shubert Organization remains today the largest theatre owner on Broadway.

New York’s fast growing Theater District had developed in many ways during the roaring twenties. It had been internationally recognized across the world as a theatrical epicenter. In 1925, as many as 80 different theatres were in operation — the industry’s all-time high — and the 1927-28 season boasted a whopping 280 new productions that graced its many stages.

It was in this time period that the Marx Brothers made their grand entrance by way of Philadelphia.

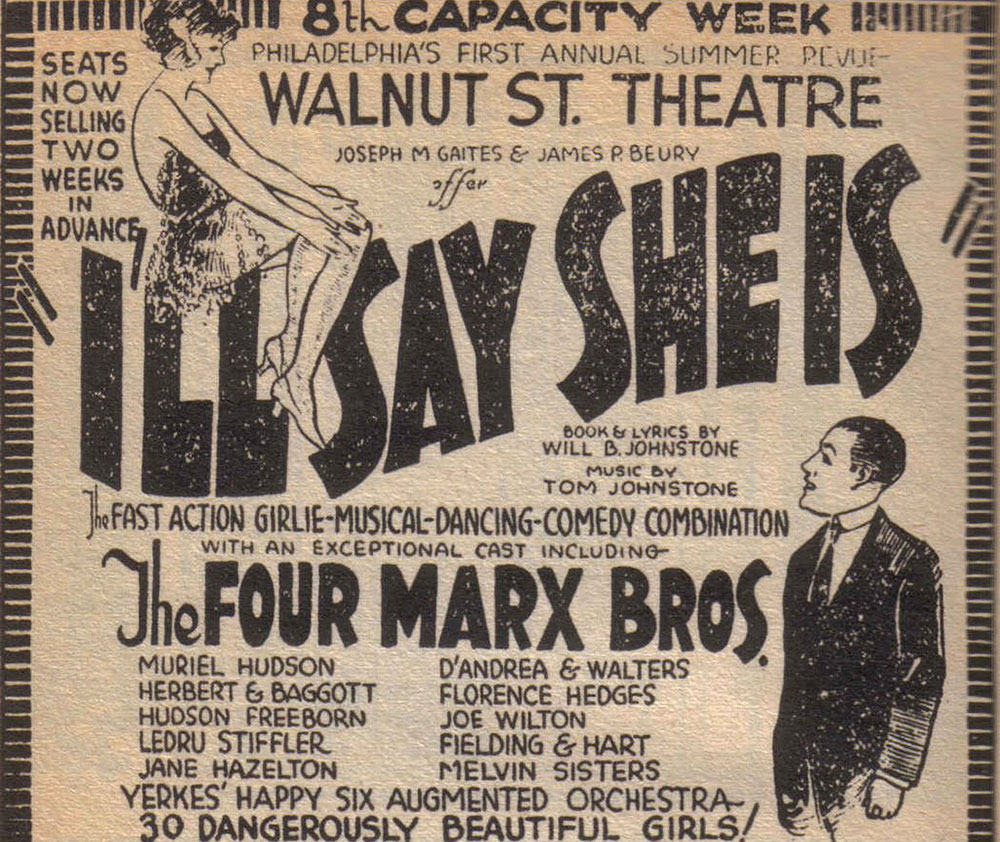

The Walnut Street Theatre in Philly was purchased by Joseph P. Beury, and he had gotten himself into a financial pickle: he only had two weeks and the scraps of defunct vaudeville shows before the theatre’s opening, and he had no act. Through a chance encounter between Beury’s producer and Chico Marx, Beury booked the Marx Brothers to perform a revue. They stitched together a storyline from their old vaudevillian performances and used the theatre’s leftover set scraps to create a show. Groucho wrote in his autobiography, Groucho and Me, “There was hardly a show that had been on Broadway in the preceding 20 years that wasn’t represented in the assortment of leftovers. There were pieces of scenery from The Girl of the Golden West, The Squaw Man, Way Down East, Turn to the Right and many others.”

The Marx Brothers became the first summer revue in Philadelphia with their show I’ll Say She Is in June 1923. Both critics and audiences were highly entertained, and the brothers had their first major hit.

They toured the show outside of Philadelphia after a few months at the Walnut Street Theatre. Catching wind of the Marx Brothers’ success, producers with the Shubert brothers hired them to mount I’ll Say She Is at the Casino Theatre on Broadway. Though the brothers’ act was one among many on the great white way, their show was an immediate hit, attracting packed houses and eliciting rave reviews. I’ll Say She Is ran through November for a lucrative five-month run.

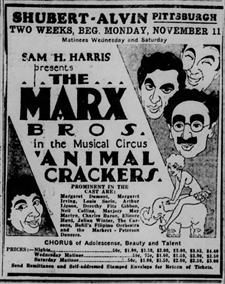

Success continued to follow the Marx Brothers on Broadway. Their second show, The Cocoanuts, opened at the Lyric Theatre in 1925 and was another immediate hit with nearly 400 performances. They took the show on the road for another two years after it closed. In 1928, they opened Animal Crackers at the 44th Street Theatre, which ran for almost 200 performances and enjoyed another road tour. They had successfully carved out their place in the big leagues of theatre.

Success continued to follow the Marx Brothers on Broadway. Their second show, The Cocoanuts, opened at the Lyric Theatre in 1925 and was another immediate hit with nearly 400 performances. They took the show on the road for another two years after it closed. In 1928, they opened Animal Crackers at the 44th Street Theatre, which ran for almost 200 performances and enjoyed another road tour. They had successfully carved out their place in the big leagues of theatre.

Within a year of opening Animal Crackers, the Marx Brothers experienced a major turning point along with the rest of the industry. The stock market crash of 1929 sent the country into economic despair and depression until the late 1930s. While folks everywhere felt the strain of financial distress, an estimated 25,000 theatre artists in New York had lost their jobs and many of Broadway’s theatres closed either temporarily or permanently.

Artists, producers and managers alike faced the difficult decision of leaving theatre altogether or heading for the burgeoning world of film on the West Coast. The movies were about to enter its now famous “golden age,” and it was one of the few soluble industries of the time. The Marx Brothers themselves had lost their fortune in the stock market crash, but depression wouldn’t follow. They took their Broadway fame and turned it into box office gold in Hollywood.

To learn about Frank Ferrante's portrayal of Groucho Marx in An Evening With Groucho at the Playhouse, visit our production detail page.

The mid-1800s saw a major shift in entertainment in New York. Vaudeville had yet to become a bonified art form, and theatre was divided evenly between the upper and lower classes. North of downtown Manhattan had been farmland, but in 1836, Mayor Cornelius Van Wyck encouraged New Yorkers to migrate further uptown to escape the crowded downtown streets and to enjoy the “clean air.” This move initiated the urban development of the city, and the region became the foundation of what is now the Theater District.

.jpg?sfvrsn=afde6080_0&MaxWidth=225&MaxHeight=&ScaleUp=false&Quality=High&Method=ResizeFitToAreaArguments&Signature=A6A17A01CAC0D75B4258B97B7FDB01A3B3AC371E) Early Broadway heavyweights like Oscar Hammerstein were among the first to create the district. Hammerstein built two theatres in the region, and by 1900, the number of theatres on Broadway had increased to 20. Now historic buildings such as the Lyceum Theatre and the New Amsterdam Theatre (which are still in operation) were built in this time period and helped foster the growth of the city’s performing arts. Vaudeville filled the stages, and soon a newly popular performance style would emerge in the revue — a similar form of song and dance variety that featured glitzy, comical and sometimes scandalous performers. With its emphasis on music, the revue offered entrée for such legendary musicians as Ira and George Gershwin, and Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart of Rogers and Hart.

Early Broadway heavyweights like Oscar Hammerstein were among the first to create the district. Hammerstein built two theatres in the region, and by 1900, the number of theatres on Broadway had increased to 20. Now historic buildings such as the Lyceum Theatre and the New Amsterdam Theatre (which are still in operation) were built in this time period and helped foster the growth of the city’s performing arts. Vaudeville filled the stages, and soon a newly popular performance style would emerge in the revue — a similar form of song and dance variety that featured glitzy, comical and sometimes scandalous performers. With its emphasis on music, the revue offered entrée for such legendary musicians as Ira and George Gershwin, and Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart of Rogers and Hart.

At the turn of the century, brothers Sam, Lee and Jacob Shubert began to acquire several different theatres and produce successful and popular shows. They were highly instrumental in creating noteworthy buzz that elevated Broadway’s reputation. In addition, they bought and operated theatres across the country. By the mid-1920s, they had owned, managed or booked more than a thousand houses in the nation. The Shubert Organization remains today the largest theatre owner on Broadway.

New York’s fast growing Theater District had developed in many ways during the roaring twenties. It had been internationally recognized across the world as a theatrical epicenter. In 1925, as many as 80 different theatres were in operation — the industry’s all-time high — and the 1927-28 season boasted a whopping 280 new productions that graced its many stages.

It was in this time period that the Marx Brothers made their grand entrance by way of Philadelphia.

The Walnut Street Theatre in Philly was purchased by Joseph P. Beury, and he had gotten himself into a financial pickle: he only had two weeks and the scraps of defunct vaudeville shows before the theatre’s opening, and he had no act. Through a chance encounter between Beury’s producer and Chico Marx, Beury booked the Marx Brothers to perform a revue. They stitched together a storyline from their old vaudevillian performances and used the theatre’s leftover set scraps to create a show. Groucho wrote in his autobiography, Groucho and Me, “There was hardly a show that had been on Broadway in the preceding 20 years that wasn’t represented in the assortment of leftovers. There were pieces of scenery from The Girl of the Golden West, The Squaw Man, Way Down East, Turn to the Right and many others.”

The cast of I'll Say She Is, 1923.

The Marx Brothers became the first summer revue in Philadelphia with their show I’ll Say She Is in June 1923. Both critics and audiences were highly entertained, and the brothers had their first major hit.

They toured the show outside of Philadelphia after a few months at the Walnut Street Theatre. Catching wind of the Marx Brothers’ success, producers with the Shubert brothers hired them to mount I’ll Say She Is at the Casino Theatre on Broadway. Though the brothers’ act was one among many on the great white way, their show was an immediate hit, attracting packed houses and eliciting rave reviews. I’ll Say She Is ran through November for a lucrative five-month run.

Success continued to follow the Marx Brothers on Broadway. Their second show, The Cocoanuts, opened at the Lyric Theatre in 1925 and was another immediate hit with nearly 400 performances. They took the show on the road for another two years after it closed. In 1928, they opened Animal Crackers at the 44th Street Theatre, which ran for almost 200 performances and enjoyed another road tour. They had successfully carved out their place in the big leagues of theatre.

Success continued to follow the Marx Brothers on Broadway. Their second show, The Cocoanuts, opened at the Lyric Theatre in 1925 and was another immediate hit with nearly 400 performances. They took the show on the road for another two years after it closed. In 1928, they opened Animal Crackers at the 44th Street Theatre, which ran for almost 200 performances and enjoyed another road tour. They had successfully carved out their place in the big leagues of theatre.

Within a year of opening Animal Crackers, the Marx Brothers experienced a major turning point along with the rest of the industry. The stock market crash of 1929 sent the country into economic despair and depression until the late 1930s. While folks everywhere felt the strain of financial distress, an estimated 25,000 theatre artists in New York had lost their jobs and many of Broadway’s theatres closed either temporarily or permanently.

Artists, producers and managers alike faced the difficult decision of leaving theatre altogether or heading for the burgeoning world of film on the West Coast. The movies were about to enter its now famous “golden age,” and it was one of the few soluble industries of the time. The Marx Brothers themselves had lost their fortune in the stock market crash, but depression wouldn’t follow. They took their Broadway fame and turned it into box office gold in Hollywood.

To learn about Frank Ferrante's portrayal of Groucho Marx in An Evening With Groucho at the Playhouse, visit our production detail page.