The Characters of August Wilson's TWO TRAINS RUNNING

Mar 18, 2019

Playhouse Artistic Associate Timothy Douglas shares insight into the characters’ journeys and how he directed the cast in August Wilson’s Two Trains Running. The writing below reflects Douglas’ own descriptions.

It is essential to me that each character in a story is working to their full potential. One of the foundations of naturalistic drama is conflict, and characters are after something. It’s very common that they don’t ultimately achieve what they say they set out to do, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t achieve other things, that they don’t go to the next level of their evolution. And that’s important to me — that every character has that parallel journey, no matter how large or how small the role is.

August Wilson’s plays in the place of American theatre have done an amazing and brilliant thing in that he has authentically placed black American lives onstage in a way that holds its own against not only the greatest American playwrights but world playwrights. And yet it remains specifically black. Unfortunately, for so many American audiences, the majority of what we know about black lives in America, we see in the media, and all too often law enforcement is involved, all too often it’s shining a harsh light on the challenges of African Americans, and it rarely goes into a deeper discussion about why we are where we are as a nation.

It’s so easy then, when we come to the theatre and see black lives onstage, we bring our biases — we bring our biases to whatever. And so, if I’m of the mind that these people have two strikes against them already, I’m looking at them kind of through a victim lens, something like that, and all too often, even in the theatre — I sometimes am guilty of that myself if I’m not really awake — I will sort of default to the intimate knowledge that I have about black life in America and the extra that it takes just to survive. We should acknowledge that. But there is an individual inside each of these characters. And no matter what the given circumstances, these individuals are striving to get ahead. And so, I feel that my job as a director is to not only reveal August Wilson’s world in its fullness and in its integrity and aspects of storytelling that he is after, underneath that, I have to make sure that driving through each character is that they’re looking at their lives past the given circumstances of the play.

Two Trains Running takes place in Memphis’ restaurant, something he worked very hard to get — talk about small business, something very relevant right now. That’s the other thing, the conversations happening onstage in this play, even though set in the 1960s, written in the 1980s, are so completely relevant for many reasons… Memphis provides not only his services as a restaurateur for this community — it’s nothing fancy, he serves the community — but he also provides a community center. When we come into the play, we hear about the movement of an urban renewal planning process that, in this phase, they are identifying buildings to be torn down for further development, and Memphis gets his notice.

So, he’s trying to get a deal that he can get out with some kind of livelihood. But there’s also this tension of, “We will lose this community center. What happens to the community when this building and this restaurant no longer exists?” So, Memphis is riding that double-edged sword, looking to move to the next phase of his life, one that we call “the golden years,” if one has that privilege. But that he has to find a way to take care of himself and yet he’s very conscious of his friends, his family, his community, and he is aware of the service that this restaurant provides. And as the discussions continue throughout the play — “What are you going to do when you sell this building?” That question keeps coming up. “What happens to the rest of us?” Memphis has to decide, through the journey of this play, where his greatest allegiance lies. Is it to his next phase of life first, or is it first to his community that he himself and his restaurant has fostered?

Wolf is a survivor. Wolf is, one would describe, a “colorful character.” But he serves a purpose. He is the numbers runner. I don’t know how many people know what a numbers runner is — it’s the closest to what we have is now the sanctioned lottery. But it was definitely a community, inside-driven event, although very popular not just in black communities but very popular in black communities before lotteries became sanctioned by the state.

So, he provides an opportunity. Small gambling. Certainly, in this community, if one hits — that’s when they win, that’s the term — that money definitely comes in handy. You know, no one’s getting rich off of hitting the numbers, but it certainly eases the pressure of living life in the late 1960s in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. So, this is just one of those examples where we can look at Wolf and, technically, he’s breaking the law. But in terms of his day-to-day life and his importance to the community, he’s moving commerce. He’s absolutely providing opportunity, but in a way that no one’s going broke. And because we have this sort of hand-to-mouth reality of this community, we don’t have the issue of people gambling beyond their means. They can actually only gamble what they have. He is also one who interacts with the community on a daily basis. He, in that respect, is a town crier. He is constantly coming into Memphis’ restaurant and bringing the news of the community. So, even those who don’t frequent Memphis’ restaurant, they are also looked after. So, there’s Wolf: community service provider.

Holloway is the seer and the knower. He is the elder in this particular community in August Wilson’s play. And in both the way that it’s structured in the play and in this production, he has a prime spot in the restaurant where he can observe all — both what’s happening in the restaurant and what’s happening outside in the district. He has become a humanistic sage, merely by his longevity. The life expectancy of a black man in America is not as high in years as a lot of other demographics, and the fact that he’s made it as long as he has is its own accomplishment. And in that way, he has become an advisor. It’s ad hoc, but people do seek his advice. He offers his advice unsolicited, but it’s all based on his observation.

Risa remains the most fascinating character for me. She is the only woman in the play. August Wilson wrote very few women throughout the cycle. And he spoke to that, and he said he’s not going to pretend intimately how a woman ticks. He has a great love of women, he appreciates women. He understands the formidable presence of women in his life, particularly his mother, who he was so devoted to, who really had such a firm hand in bringing him up. And so, it’s challenging for women in August Wilson’s casts — especially in this one where she’s the only one. Who does she talk to about things that are not for men during this process? I pay very particular attention and I give her a lot of space.

Risa, also, has a particular character choice that she’s made — and this is revealed pretty early on in the play — she has cut into her legs. We didn’t call it cutting in 1969, it wasn’t a known phenomenon then, but that’s what we would call it today. But she did it quite deliberately. And she wanted to be taken on her own terms. She recognized that the way most men in the world treat most women is as objects. As something to be conquered. As a sexual conquest. And that seems to be the norm in 1969 America. And she knew — she instinctively knew she was more than that and demanded to be seen as such. However she got to it, the choice she made was to mutilate physical self, knowing that that was going to force men to actually deal with her — either by not dealing with her at all, they’re gone and no longer being a pain in the butt to her, or they’re going to have to look up and deal with this woman with organic curiosity. And as a result of this act — and we all have our judgments about self-mutilation, but she succeeded, in that one act, in forcing everyone in her world to treat her as an individual. And the lessons that she garners through her life, through her world, she gets to fully self-actualize. Now, what’s paradoxical about that is she succeeded in removing herself as the object of men’s desire and fantasy, but now she’s this whole person, regardless of gender, in a world that is not fully receiving black people, not fully receiving women and, my goodness, certainly not receiving a black woman. So, she has all this innate power — what the heck does she do with it?

Sterling walks into this world and he is the stranger. And his journey is quite unique as well. He, in his way and his life choices, has become self-actualized in a parallel and potent way to Risa. And so energetically, the instant they meet — I won’t call it “love at first sight,” I’ll call it “acknowledgement at first sight.” Acknowledgement of a fully formed person. And what’s really interesting about that is, to be that sort of person living on the edge, without that many people in your life, who share the experience — it’s not a commonality that feels unique — one is often lonely and has gotten used to that. So, when you meet your counterpart, then suddenly you’re pulled into the unknown again because I recognize something in you. I see that you see me, I have been yearning and waiting for this, but I’ve learned to live without it. So, what is the impact that I have to give up in order to receive you and to be received? And for me, that is the journey of Risa and Sterling in the middle of this world of Two Trains Running.

West is the longest-standing business owner in the community and he is still holding on to his place. He’s the funeral director. And he at once anchors this community. He’s a regular dweller in Memphis’ restaurant, but there is also that thing that certainly I carry and many people carry around those that handle the dead. Even in the 1960s, America has become a culture that doesn’t want to deal with death as a natural part of life, and that we send the illness and the bodies to the undertaker who makes them look like they’re still alive — or some believe that that’s the goal. And we have that level of detachment, so what’s interesting about West’s presence: at once being such a stalwart in the community but at the same time there is that level of being a little creeped out by him. There’s an interesting dichotomy. And ironically, it is West who offers the denizens of the café and the audience the most wonderful philosophy and bridge by those of us who are repelled by death towards understanding its natural part of the full life cycle.

Hambone represents the ultimate commitment to justice as promised by the U.S. Constitution and also the human, innate moral sense of justice if we actually choose to listen and practice that. Interestingly, Hambone is limited to one phrase. A great wrong has been dealt him nine years prior to when the play began. And his pursuit of righting that wrong has quite literally driven him out of his mind. I won’t say that he’s crazy because I don’t think that he’s crazy, but he is literally out of the mind where he entered and believed that he would receive justice, just by right of being an American citizen. And so, for nearly 10 years, with a single, passionate phrase that is the most passionate seeking of justice — and I won’t give away his phrase — he is a compelling reminder to all of us our duty as citizens within a community and our duty as Americans. And he’s a constant confrontation to each of us and where we sit with that — how are committed are we and how much are we a part of leaning into the solution? When someone like Hambone comes through the room, with his single phrase of seeking justice, everything stops. It’s like stopping a clock. And I believe he has that impact on the audience as well. So, this character can be dismissed as a kook who comes through the restaurant every day, but I saw so much more than that.

To learn more about the Playhouse’s production of August Wilson’s Two Trains Running, visit our production detail page.

The cast of August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

It is essential to me that each character in a story is working to their full potential. One of the foundations of naturalistic drama is conflict, and characters are after something. It’s very common that they don’t ultimately achieve what they say they set out to do, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t achieve other things, that they don’t go to the next level of their evolution. And that’s important to me — that every character has that parallel journey, no matter how large or how small the role is.

August Wilson’s plays in the place of American theatre have done an amazing and brilliant thing in that he has authentically placed black American lives onstage in a way that holds its own against not only the greatest American playwrights but world playwrights. And yet it remains specifically black. Unfortunately, for so many American audiences, the majority of what we know about black lives in America, we see in the media, and all too often law enforcement is involved, all too often it’s shining a harsh light on the challenges of African Americans, and it rarely goes into a deeper discussion about why we are where we are as a nation.

It’s so easy then, when we come to the theatre and see black lives onstage, we bring our biases — we bring our biases to whatever. And so, if I’m of the mind that these people have two strikes against them already, I’m looking at them kind of through a victim lens, something like that, and all too often, even in the theatre — I sometimes am guilty of that myself if I’m not really awake — I will sort of default to the intimate knowledge that I have about black life in America and the extra that it takes just to survive. We should acknowledge that. But there is an individual inside each of these characters. And no matter what the given circumstances, these individuals are striving to get ahead. And so, I feel that my job as a director is to not only reveal August Wilson’s world in its fullness and in its integrity and aspects of storytelling that he is after, underneath that, I have to make sure that driving through each character is that they’re looking at their lives past the given circumstances of the play.

Memphis

Raymond Anthony Thomas in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Two Trains Running takes place in Memphis’ restaurant, something he worked very hard to get — talk about small business, something very relevant right now. That’s the other thing, the conversations happening onstage in this play, even though set in the 1960s, written in the 1980s, are so completely relevant for many reasons… Memphis provides not only his services as a restaurateur for this community — it’s nothing fancy, he serves the community — but he also provides a community center. When we come into the play, we hear about the movement of an urban renewal planning process that, in this phase, they are identifying buildings to be torn down for further development, and Memphis gets his notice.

So, he’s trying to get a deal that he can get out with some kind of livelihood. But there’s also this tension of, “We will lose this community center. What happens to the community when this building and this restaurant no longer exists?” So, Memphis is riding that double-edged sword, looking to move to the next phase of his life, one that we call “the golden years,” if one has that privilege. But that he has to find a way to take care of himself and yet he’s very conscious of his friends, his family, his community, and he is aware of the service that this restaurant provides. And as the discussions continue throughout the play — “What are you going to do when you sell this building?” That question keeps coming up. “What happens to the rest of us?” Memphis has to decide, through the journey of this play, where his greatest allegiance lies. Is it to his next phase of life first, or is it first to his community that he himself and his restaurant has fostered?

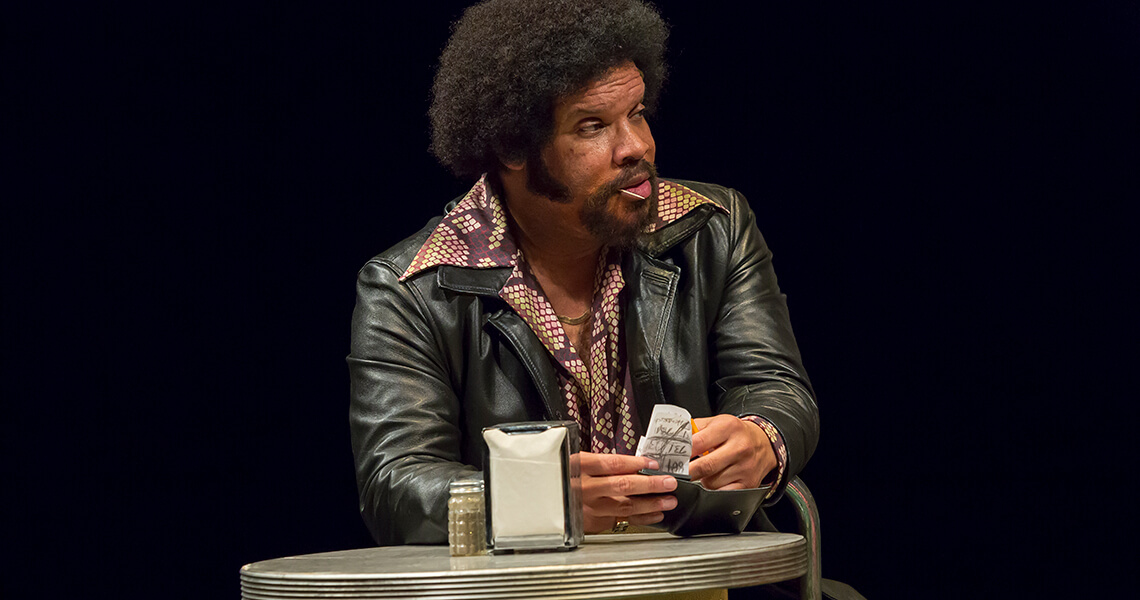

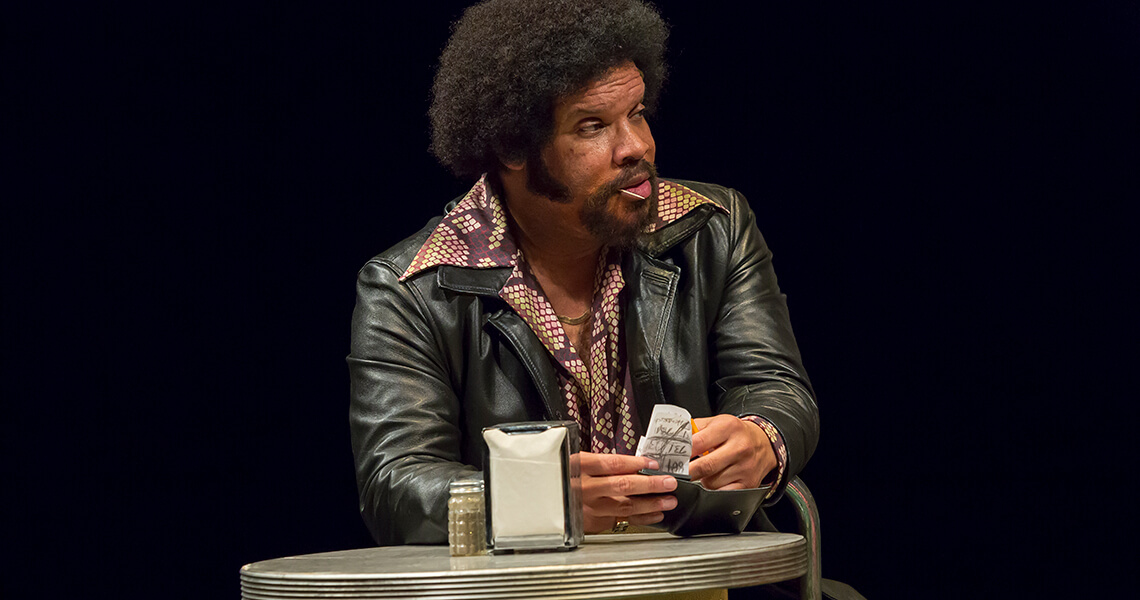

Wolf

Jefferson A. Russell in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Wolf is a survivor. Wolf is, one would describe, a “colorful character.” But he serves a purpose. He is the numbers runner. I don’t know how many people know what a numbers runner is — it’s the closest to what we have is now the sanctioned lottery. But it was definitely a community, inside-driven event, although very popular not just in black communities but very popular in black communities before lotteries became sanctioned by the state.

So, he provides an opportunity. Small gambling. Certainly, in this community, if one hits — that’s when they win, that’s the term — that money definitely comes in handy. You know, no one’s getting rich off of hitting the numbers, but it certainly eases the pressure of living life in the late 1960s in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. So, this is just one of those examples where we can look at Wolf and, technically, he’s breaking the law. But in terms of his day-to-day life and his importance to the community, he’s moving commerce. He’s absolutely providing opportunity, but in a way that no one’s going broke. And because we have this sort of hand-to-mouth reality of this community, we don’t have the issue of people gambling beyond their means. They can actually only gamble what they have. He is also one who interacts with the community on a daily basis. He, in that respect, is a town crier. He is constantly coming into Memphis’ restaurant and bringing the news of the community. So, even those who don’t frequent Memphis’ restaurant, they are also looked after. So, there’s Wolf: community service provider.

Holloway

Michael Anthony Williams in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Holloway is the seer and the knower. He is the elder in this particular community in August Wilson’s play. And in both the way that it’s structured in the play and in this production, he has a prime spot in the restaurant where he can observe all — both what’s happening in the restaurant and what’s happening outside in the district. He has become a humanistic sage, merely by his longevity. The life expectancy of a black man in America is not as high in years as a lot of other demographics, and the fact that he’s made it as long as he has is its own accomplishment. And in that way, he has become an advisor. It’s ad hoc, but people do seek his advice. He offers his advice unsolicited, but it’s all based on his observation.

Risa

Malkia Stampley in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Risa remains the most fascinating character for me. She is the only woman in the play. August Wilson wrote very few women throughout the cycle. And he spoke to that, and he said he’s not going to pretend intimately how a woman ticks. He has a great love of women, he appreciates women. He understands the formidable presence of women in his life, particularly his mother, who he was so devoted to, who really had such a firm hand in bringing him up. And so, it’s challenging for women in August Wilson’s casts — especially in this one where she’s the only one. Who does she talk to about things that are not for men during this process? I pay very particular attention and I give her a lot of space.

Risa, also, has a particular character choice that she’s made — and this is revealed pretty early on in the play — she has cut into her legs. We didn’t call it cutting in 1969, it wasn’t a known phenomenon then, but that’s what we would call it today. But she did it quite deliberately. And she wanted to be taken on her own terms. She recognized that the way most men in the world treat most women is as objects. As something to be conquered. As a sexual conquest. And that seems to be the norm in 1969 America. And she knew — she instinctively knew she was more than that and demanded to be seen as such. However she got to it, the choice she made was to mutilate physical self, knowing that that was going to force men to actually deal with her — either by not dealing with her at all, they’re gone and no longer being a pain in the butt to her, or they’re going to have to look up and deal with this woman with organic curiosity. And as a result of this act — and we all have our judgments about self-mutilation, but she succeeded, in that one act, in forcing everyone in her world to treat her as an individual. And the lessons that she garners through her life, through her world, she gets to fully self-actualize. Now, what’s paradoxical about that is she succeeded in removing herself as the object of men’s desire and fantasy, but now she’s this whole person, regardless of gender, in a world that is not fully receiving black people, not fully receiving women and, my goodness, certainly not receiving a black woman. So, she has all this innate power — what the heck does she do with it?

Sterling

Chiké Johnson and Malkia Stampley in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Sterling walks into this world and he is the stranger. And his journey is quite unique as well. He, in his way and his life choices, has become self-actualized in a parallel and potent way to Risa. And so energetically, the instant they meet — I won’t call it “love at first sight,” I’ll call it “acknowledgement at first sight.” Acknowledgement of a fully formed person. And what’s really interesting about that is, to be that sort of person living on the edge, without that many people in your life, who share the experience — it’s not a commonality that feels unique — one is often lonely and has gotten used to that. So, when you meet your counterpart, then suddenly you’re pulled into the unknown again because I recognize something in you. I see that you see me, I have been yearning and waiting for this, but I’ve learned to live without it. So, what is the impact that I have to give up in order to receive you and to be received? And for me, that is the journey of Risa and Sterling in the middle of this world of Two Trains Running.

West

Doug Brown in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

West is the longest-standing business owner in the community and he is still holding on to his place. He’s the funeral director. And he at once anchors this community. He’s a regular dweller in Memphis’ restaurant, but there is also that thing that certainly I carry and many people carry around those that handle the dead. Even in the 1960s, America has become a culture that doesn’t want to deal with death as a natural part of life, and that we send the illness and the bodies to the undertaker who makes them look like they’re still alive — or some believe that that’s the goal. And we have that level of detachment, so what’s interesting about West’s presence: at once being such a stalwart in the community but at the same time there is that level of being a little creeped out by him. There’s an interesting dichotomy. And ironically, it is West who offers the denizens of the café and the audience the most wonderful philosophy and bridge by those of us who are repelled by death towards understanding its natural part of the full life cycle.

Hambone

Chiké Johnson, Frank Britton and Michael Anthony Williams in August Wilson's Two Trains Running. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Hambone represents the ultimate commitment to justice as promised by the U.S. Constitution and also the human, innate moral sense of justice if we actually choose to listen and practice that. Interestingly, Hambone is limited to one phrase. A great wrong has been dealt him nine years prior to when the play began. And his pursuit of righting that wrong has quite literally driven him out of his mind. I won’t say that he’s crazy because I don’t think that he’s crazy, but he is literally out of the mind where he entered and believed that he would receive justice, just by right of being an American citizen. And so, for nearly 10 years, with a single, passionate phrase that is the most passionate seeking of justice — and I won’t give away his phrase — he is a compelling reminder to all of us our duty as citizens within a community and our duty as Americans. And he’s a constant confrontation to each of us and where we sit with that — how are committed are we and how much are we a part of leaning into the solution? When someone like Hambone comes through the room, with his single phrase of seeking justice, everything stops. It’s like stopping a clock. And I believe he has that impact on the audience as well. So, this character can be dismissed as a kook who comes through the restaurant every day, but I saw so much more than that.

To learn more about the Playhouse’s production of August Wilson’s Two Trains Running, visit our production detail page.