Conveying Truths: A Q&A With Timothy Douglas

February 15, 2019

Playhouse Associate Artist Timothy Douglas provides creative insight into directing August Wilson’s Two Trains Running.

Timothy is a recent recipient of the National Black Theatre Festival/Lloyd Richards’ Directing Award. His previous Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park directing credits include The Last Firefly, Jitney, Mothers and Sons, Buzzer, the world premiere of Keith Josef Adkins’ Safe House, The North Pool, Clybourne Park and The Trip to Bountiful. Most recently The New York Times sited his off-Broadway production of Dael Orlandersmith’s Yellowman as one of their readers’ top-ten picks for 2018. For Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., he has directed Nina Simone: Four Women, King Hedley II and Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Disgraced, which also toured five cities in China last year. Representative productions include The Color Purple (Portland Center Stage); August Wilson’s Gem Of The Ocean and Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 (Round House Theatre); Dontrell Who Kissed the Sea (Theater Alliance in D.C., six 2016 Helen Hayes Award nominations); Richard II (Shakespeare & Company); the world premiere of August Wilson's Radio Golf (Yale Repertory Theatre); his acclaimed Caribbean-inspired Much Ado About Nothing (Folger Theatre); and the world premiere of Rajiv Joseph's The Lake Effect (Silk Road Rising in Chicago, 2013 Jeff Award for Best New Work). For three seasons Timothy served as associate artistic director at Actors Theatre of Louisville and has also directed more than 100 projects for theatre companies nationally and abroad, including American Conservatory Theater, Guthrie Theater, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, South Coast Repertory, Portland Center Stage, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, PlayMakers Repertory Company, San Jose Repertory Theatre, Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Indiana Repertory Theatre, Magic Theatre, Pioneer Theatre Company, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Downstage (New Zealand), National Theatre (Norway) and Milwaukee Repertory Theater. Timothy is a graduate of the acting program at Yale School of Drama. To learn more, visit www.TimothyDouglas.org.

Timothy is a recent recipient of the National Black Theatre Festival/Lloyd Richards’ Directing Award. His previous Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park directing credits include The Last Firefly, Jitney, Mothers and Sons, Buzzer, the world premiere of Keith Josef Adkins’ Safe House, The North Pool, Clybourne Park and The Trip to Bountiful. Most recently The New York Times sited his off-Broadway production of Dael Orlandersmith’s Yellowman as one of their readers’ top-ten picks for 2018. For Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., he has directed Nina Simone: Four Women, King Hedley II and Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Disgraced, which also toured five cities in China last year. Representative productions include The Color Purple (Portland Center Stage); August Wilson’s Gem Of The Ocean and Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 (Round House Theatre); Dontrell Who Kissed the Sea (Theater Alliance in D.C., six 2016 Helen Hayes Award nominations); Richard II (Shakespeare & Company); the world premiere of August Wilson's Radio Golf (Yale Repertory Theatre); his acclaimed Caribbean-inspired Much Ado About Nothing (Folger Theatre); and the world premiere of Rajiv Joseph's The Lake Effect (Silk Road Rising in Chicago, 2013 Jeff Award for Best New Work). For three seasons Timothy served as associate artistic director at Actors Theatre of Louisville and has also directed more than 100 projects for theatre companies nationally and abroad, including American Conservatory Theater, Guthrie Theater, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, South Coast Repertory, Portland Center Stage, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, PlayMakers Repertory Company, San Jose Repertory Theatre, Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Indiana Repertory Theatre, Magic Theatre, Pioneer Theatre Company, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Downstage (New Zealand), National Theatre (Norway) and Milwaukee Repertory Theater. Timothy is a graduate of the acting program at Yale School of Drama. To learn more, visit www.TimothyDouglas.org.

August Wilson is widely regarded as the world’s preeminent African-American playwright and one of the most influential voices in the history of theatre. His stories feature richly drawn portraits of multidimensional characters, as well as monologues that critics have praised as “verbal poetry.” In your opinion, what makes Wilson’s work so enduring?

Although there are some accomplished and iconic African-American playwrights (Ed Bullins, Alice Childress, James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka and Lorraine Hansberry) who precede August Wilson, it is my estimation that his singular, breakthrough talent lay in his ability to organize a divinely perfect construction of words that captures and articulates the exponentially complicated nature of what is to be black in America with mathematical exactness — and he is able to accomplish communicating these vulnerable and incendiary truths without it ever becoming a diatribe against dominant culture. August Wilson’s works are unapologetically pro-black, which is the polar opposite of being anti-white, and it is because of this reality — by way of his plays, characters and dynamic use of language — he is able to convey universal truths.

You have extensive experience with Wilson’s plays, having directed Fences, Radio Golf, The Piano Lesson, Seven Guitars, King Hedley II and others. Why do you personally feel drawn to this body of work?

To be candid, being drawn to these plays is not something I’ve really had much of a choice in. When August Wilson’s plays first came on to the scene, one of the major impacts was in filling the void that was the lack of authentic black lives and voices on mainstream American stages. Mr. Wilson remained committed that these plays would land with genuine and enduring integrity and was adamant that black directors be the ones to helm his plays in order to enhance their intended cultural and social authenticity. Once I made the transition from acting to directing, you could count on one hand the number of black directors working on mainstream American stages, and because of the American Century Cycle, there literally were not enough directors to fill the slots. As long as I wanted to be a “working director,” it became a given that the lion’s share of the productions I would direct are Wilson’s.

When speaking about the Playhouse’s production of Jitney in 2016, you invited audiences to see themselves in the characters of the play. Do you make the same invitation for Two Trains Running? Is there a character you particularly relate to?

To be specific, at that moment of invitation, I was speaking to a room comprised of a majority of white people and was mindful of my (potentially erroneous) assumption that for them there was a collective dearth of integrated experiences and/or regular interaction with black people. When this is the prevailing reality within audiences, I find that all too often Wilson’s very American plays can feel like “other,” which can then unintentionally distance the audience from the story and the lives unfolding on the stage. No matter what I’m directing, I strive to make the experience as personal as possible, and specifically in the case of Jitney and Two Trains Running, it becomes far easier for the Cincinnati audience to access the world of the entire play when focused on a particular character, who in turn will also serve as their way-shower to the world of the play. I currently find myself particularly focused on Risa, who by far is the most interesting — as well as elusive — character in the play. I’m thoroughly intrigued by her being the only woman in a male-dominated world and how expertly she single-handedly balances them all.

Two Trains Running is set in the 1960s against the backdrop of the civil rights movement. Are there any specific issues in the play that feel especially relevant in 2019?

Among Two Trains Running’s seismic themes, one of the most resonant is the specter of “eminent domain” threatening the livelihood of the denizens of Memphis’ diner, as well as tearing at the very fabric of this Pittsburgh Hill District’s African-American community at large. Even though the play is set in 1969, it nonetheless shines a potent parallel light on the intense growing pains of America’s aggressive urban renewal movement, which Cincinnati audiences will recognize in its ongoing challenges with the navigation of the gentrification in full swing here.

To learn more about the Playhouse's production of August Wilson's Two Trains Running, visit our production detail page.

Timothy is a recent recipient of the National Black Theatre Festival/Lloyd Richards’ Directing Award. His previous Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park directing credits include The Last Firefly, Jitney, Mothers and Sons, Buzzer, the world premiere of Keith Josef Adkins’ Safe House, The North Pool, Clybourne Park and The Trip to Bountiful. Most recently The New York Times sited his off-Broadway production of Dael Orlandersmith’s Yellowman as one of their readers’ top-ten picks for 2018. For Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., he has directed Nina Simone: Four Women, King Hedley II and Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Disgraced, which also toured five cities in China last year. Representative productions include The Color Purple (Portland Center Stage); August Wilson’s Gem Of The Ocean and Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 (Round House Theatre); Dontrell Who Kissed the Sea (Theater Alliance in D.C., six 2016 Helen Hayes Award nominations); Richard II (Shakespeare & Company); the world premiere of August Wilson's Radio Golf (Yale Repertory Theatre); his acclaimed Caribbean-inspired Much Ado About Nothing (Folger Theatre); and the world premiere of Rajiv Joseph's The Lake Effect (Silk Road Rising in Chicago, 2013 Jeff Award for Best New Work). For three seasons Timothy served as associate artistic director at Actors Theatre of Louisville and has also directed more than 100 projects for theatre companies nationally and abroad, including American Conservatory Theater, Guthrie Theater, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, South Coast Repertory, Portland Center Stage, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, PlayMakers Repertory Company, San Jose Repertory Theatre, Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Indiana Repertory Theatre, Magic Theatre, Pioneer Theatre Company, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Downstage (New Zealand), National Theatre (Norway) and Milwaukee Repertory Theater. Timothy is a graduate of the acting program at Yale School of Drama. To learn more, visit www.TimothyDouglas.org.

Timothy is a recent recipient of the National Black Theatre Festival/Lloyd Richards’ Directing Award. His previous Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park directing credits include The Last Firefly, Jitney, Mothers and Sons, Buzzer, the world premiere of Keith Josef Adkins’ Safe House, The North Pool, Clybourne Park and The Trip to Bountiful. Most recently The New York Times sited his off-Broadway production of Dael Orlandersmith’s Yellowman as one of their readers’ top-ten picks for 2018. For Arena Stage in Washington, D.C., he has directed Nina Simone: Four Women, King Hedley II and Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Disgraced, which also toured five cities in China last year. Representative productions include The Color Purple (Portland Center Stage); August Wilson’s Gem Of The Ocean and Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 (Round House Theatre); Dontrell Who Kissed the Sea (Theater Alliance in D.C., six 2016 Helen Hayes Award nominations); Richard II (Shakespeare & Company); the world premiere of August Wilson's Radio Golf (Yale Repertory Theatre); his acclaimed Caribbean-inspired Much Ado About Nothing (Folger Theatre); and the world premiere of Rajiv Joseph's The Lake Effect (Silk Road Rising in Chicago, 2013 Jeff Award for Best New Work). For three seasons Timothy served as associate artistic director at Actors Theatre of Louisville and has also directed more than 100 projects for theatre companies nationally and abroad, including American Conservatory Theater, Guthrie Theater, Berkeley Repertory Theatre, South Coast Repertory, Portland Center Stage, Steppenwolf Theatre Company, PlayMakers Repertory Company, San Jose Repertory Theatre, Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, Indiana Repertory Theatre, Magic Theatre, Pioneer Theatre Company, Berkshire Theatre Festival, Downstage (New Zealand), National Theatre (Norway) and Milwaukee Repertory Theater. Timothy is a graduate of the acting program at Yale School of Drama. To learn more, visit www.TimothyDouglas.org.

August Wilson is widely regarded as the world’s preeminent African-American playwright and one of the most influential voices in the history of theatre. His stories feature richly drawn portraits of multidimensional characters, as well as monologues that critics have praised as “verbal poetry.” In your opinion, what makes Wilson’s work so enduring?

Although there are some accomplished and iconic African-American playwrights (Ed Bullins, Alice Childress, James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka and Lorraine Hansberry) who precede August Wilson, it is my estimation that his singular, breakthrough talent lay in his ability to organize a divinely perfect construction of words that captures and articulates the exponentially complicated nature of what is to be black in America with mathematical exactness — and he is able to accomplish communicating these vulnerable and incendiary truths without it ever becoming a diatribe against dominant culture. August Wilson’s works are unapologetically pro-black, which is the polar opposite of being anti-white, and it is because of this reality — by way of his plays, characters and dynamic use of language — he is able to convey universal truths.

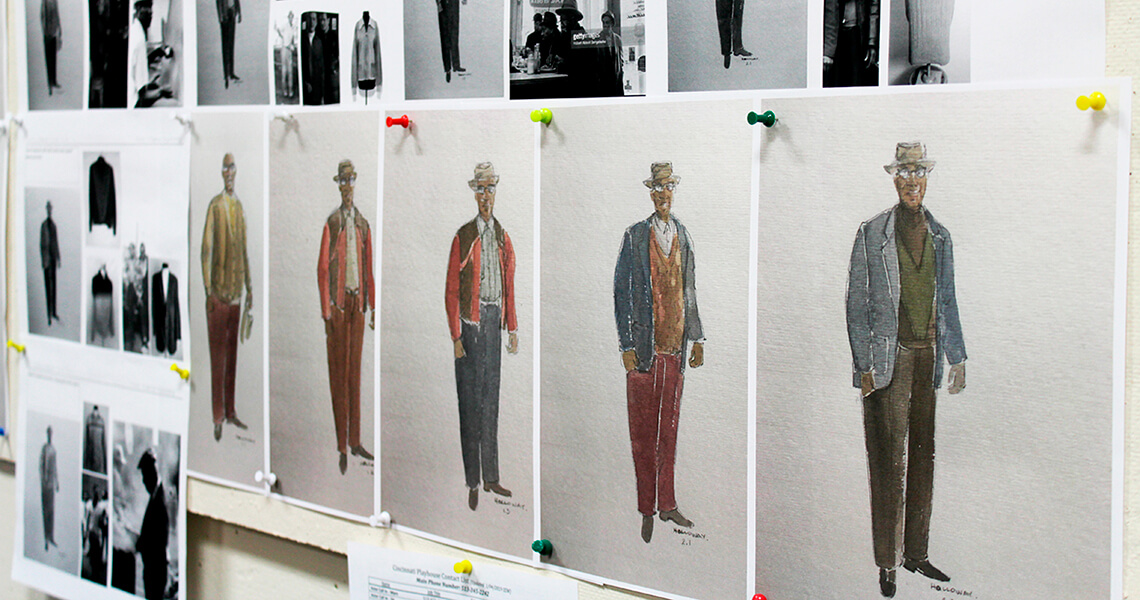

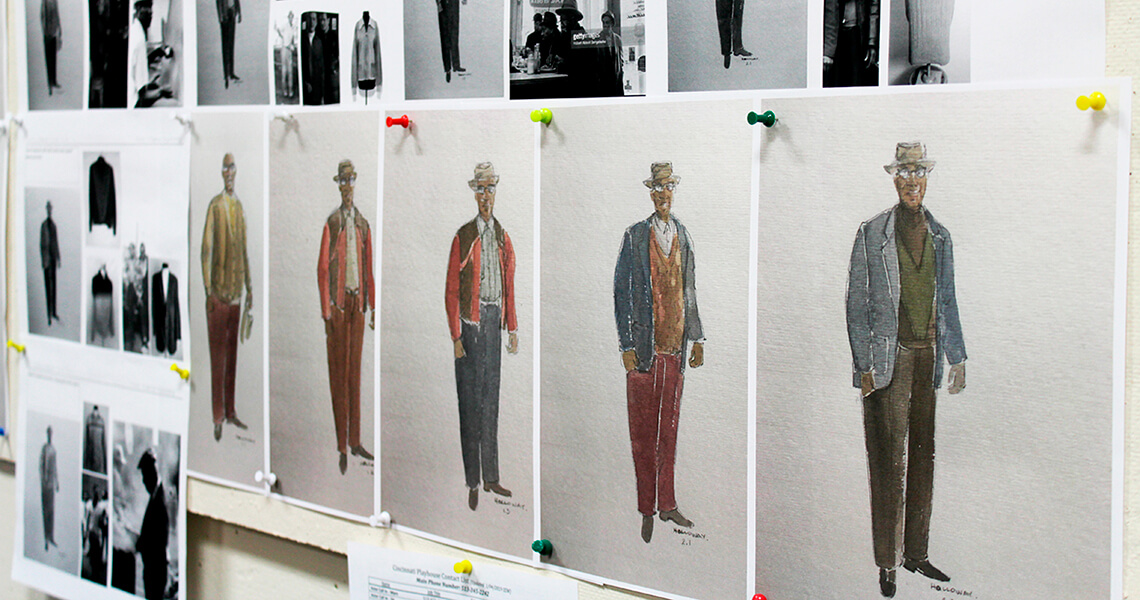

Costume renderings for August Wilson's Two Trains Running by Costume Designer Kara Harmon.

You have extensive experience with Wilson’s plays, having directed Fences, Radio Golf, The Piano Lesson, Seven Guitars, King Hedley II and others. Why do you personally feel drawn to this body of work?

To be candid, being drawn to these plays is not something I’ve really had much of a choice in. When August Wilson’s plays first came on to the scene, one of the major impacts was in filling the void that was the lack of authentic black lives and voices on mainstream American stages. Mr. Wilson remained committed that these plays would land with genuine and enduring integrity and was adamant that black directors be the ones to helm his plays in order to enhance their intended cultural and social authenticity. Once I made the transition from acting to directing, you could count on one hand the number of black directors working on mainstream American stages, and because of the American Century Cycle, there literally were not enough directors to fill the slots. As long as I wanted to be a “working director,” it became a given that the lion’s share of the productions I would direct are Wilson’s.

When speaking about the Playhouse’s production of Jitney in 2016, you invited audiences to see themselves in the characters of the play. Do you make the same invitation for Two Trains Running? Is there a character you particularly relate to?

To be specific, at that moment of invitation, I was speaking to a room comprised of a majority of white people and was mindful of my (potentially erroneous) assumption that for them there was a collective dearth of integrated experiences and/or regular interaction with black people. When this is the prevailing reality within audiences, I find that all too often Wilson’s very American plays can feel like “other,” which can then unintentionally distance the audience from the story and the lives unfolding on the stage. No matter what I’m directing, I strive to make the experience as personal as possible, and specifically in the case of Jitney and Two Trains Running, it becomes far easier for the Cincinnati audience to access the world of the entire play when focused on a particular character, who in turn will also serve as their way-shower to the world of the play. I currently find myself particularly focused on Risa, who by far is the most interesting — as well as elusive — character in the play. I’m thoroughly intrigued by her being the only woman in a male-dominated world and how expertly she single-handedly balances them all.

Michael Kevin Darnall and Dion Graham in the Playhouse's 2016 production of August Wilson's Jitney. Photo by Mikki Schaffner.

Two Trains Running is set in the 1960s against the backdrop of the civil rights movement. Are there any specific issues in the play that feel especially relevant in 2019?

Among Two Trains Running’s seismic themes, one of the most resonant is the specter of “eminent domain” threatening the livelihood of the denizens of Memphis’ diner, as well as tearing at the very fabric of this Pittsburgh Hill District’s African-American community at large. Even though the play is set in 1969, it nonetheless shines a potent parallel light on the intense growing pains of America’s aggressive urban renewal movement, which Cincinnati audiences will recognize in its ongoing challenges with the navigation of the gentrification in full swing here.

To learn more about the Playhouse's production of August Wilson's Two Trains Running, visit our production detail page.